-

Stimulated emission

Kényszerített emisszió

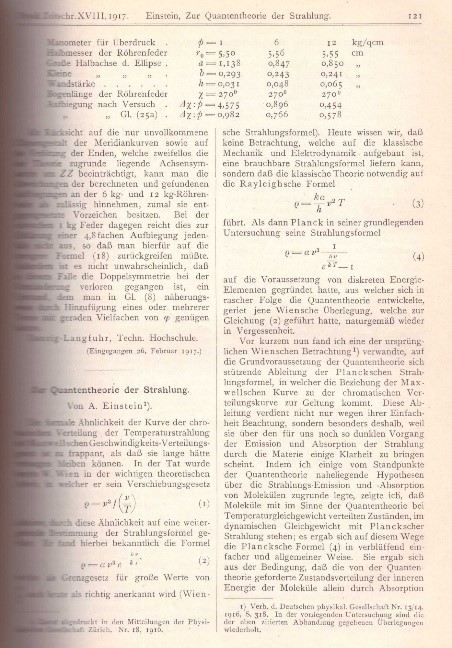

The phenomenon utilized in the production of laser light was first discussed by Albert Einstein in his 1917 paper titled The Quantum Theory of Radiation [1].

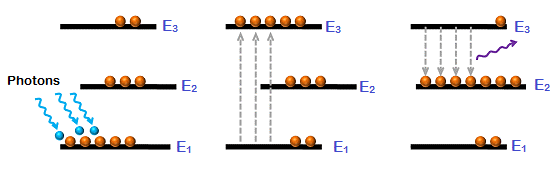

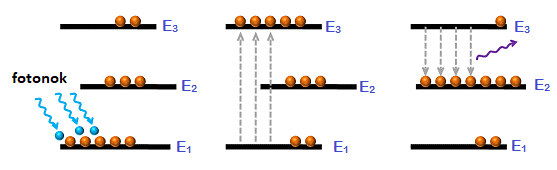

In atoms, the nucleus is surrounded by an electron cloud with electrons of various energies. The possible energy levels are determined by the laws of physics.

In the ground state, electrons in an atom occupy the lowest energy levels, but they can be forced to move to a higher energy level and get into an excited state by absorbing a sufficient amount of energy. However, this excited state is not stable and after some time the electrons will spontaneously return to their ground state. The difference between the two energy levels (the excess energy they originally gained) is emitted by electrons returning to the lower energy level in the form of light radiation.

A lézerfény előállításának elméleti alapjául szolgáló jelenséget Albert Einstein „A sugárzás kvantumelmélete” című, 1917-ben publikált cikkében tárgyalta [1].

Az atomokban az atommagot elektronfelhő veszi körül, amelyben különböző energiájú elektronok vannak. A lehetséges energiaszinteket fizikai törvények határozzák meg.

Alapállapotban az atomokban lévő elektronok a legalacsonyabb energiaszinteket töltik be, de megfelelő mennyiségű energia felvételével egy magasabb energiaszintre kerülhetnek. Ez a gerjesztett állapot azonban nem stabil: egy idő után az elektron spontán visszatér alapállapotába, és a két energiaszint közötti energia-különbséget az alacsonyabb szintre visszatérő elektron leadja. A folyamat elején felvett és a végén leadott energia egy foton formájában érkezik és egy foton formájában sugárzódik ki. A foton egy „energiacsomag”: az elektromágneses sugárzás (melynek egyik megjelenési formája a látható fény) elemi részecskéje, kvantuma.

The energy absorbed at the beginning and released at the end of the process arrives in the form of a photon, and is emitted in the form of a photon. The photon is the quantized unit of electromagnetic radiation (which takes many forms, including visible light).

This spontaneous absorption-emission process can be developed further by external intervention. Einstein predicted that if an excited atom absorbs another photon whose energy equals the exact energy of the excited state, not one but two photons are emitted when the atom returns to the ground state. During stimulated emission, the two emitted photons are coherent: they travel in the same direction with identical energy and phase.

Einstein’s theoretical prediction was later confirmed experimentally, which created the possibility for the production of laser light.

Ez a spontán abszorpciós-emissziós folyamat külső beavatkozással továbbfejleszthető. Einstein megsejtette és elméletileg igazolta, hogy ha a gerjesztett állapotban lévő atom még egy, a gerjesztett állapottal megegyező energiájú fotont vesz fel, akkor az alapállapotba való visszatéréskor nem egy, hanem két fotont sugároz ki, és e két foton egymással minden jellemzőjét tekintve megegyezik. Azt mondjuk, hogy a kényszerített emisszió folyamata során a kisugárzott két foton koherens: irányuk, energiájuk és fázisuk is azonos.

Einstein elméletileg igazolt sejtését később kísérletek is igazolták, megteremtve a lézerfény előállításának lehetőségét.

Referencia

[1] A. Einstein: Quantentheorie der Strahlung; Physikalische Zeitschrift 18 (1917) 121-128

Reference

[1] A. Einstein: Quantentheorie der Strahlung; Physikalische Zeitschrift 18 (1917) 121-128

-

Optical pumping

Optikai pumpálás

In thermal equilibrium the majority of particles in a matter are in their ground state, and the short-lived, spontaneously excited particles spontaneously relax to the ground state. To produce laser light, the majority of the particles must be in the excited state, when the number of emitted coherent photons can be increased by stimulated emission. This unusual ratio of ground-state and excited-state particles, i.e. population inversion can be achieved by giving particles sufficient energy.

Termikus egyensúlyban egy anyaghalmaz részecskéinek döntő többsége alapállapotban van, és a rövid ideig tartó spontán gerjesztett állapotból a részecskék spontán módon térnek vissza alapállapotukba. Lézerfény előállításához azonban az szükséges, hogy a részecskék túlnyomó része gerjesztett állapotú legyen, mert így kényszerített emisszióval növelhető a kibocsátott koherens fotonok száma. Az alapállapotú és gerjesztett állapotú részecskék számának ezt a szokatlan arányát, a populációinverziót úgy lehet elérni, ha a részecskék megfelelő mennyiségű energiát kapnak.

For the laser to operate, population inversion must be continuously maintained, i.e. the medium must contain more excited than relaxed particles.

A lézer működéséhez a populációinverziót nemcsak létre kell hozni, hanem fenn is kell tartani, vagyis folyamatosan biztosítani kell, hogy az anyaghalmazban több gerjesztett, mint alapállapotú részecske legyen.

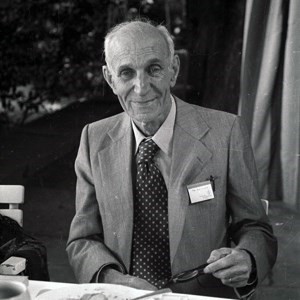

To this end, Alfred Kastler developed the method of optical pumping, during which the necessary energy was provided by a light source having sufficient power, e.g. an arc lamp, a flash tube and later, a laser.

For his research, Alfred Kastler was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1966.

Erre a célra dolgozta ki Alfred Kastler az optikai pumpálás módszerét, amelynek során a szükséges energiát egy megfelelő teljesítményű fényforrás, például ívlámpa, villanólámpa, majd később lézer szolgáltatja.

Kutatásaiért Alfred Kastler 1966-ban Nobel díjat kapott.

Referencia

A. Kastler: Quelques suggestions concernant la production optique et la détection optique d'une inégalité de population des niveaux de quantifigation spatiale des atomes. Application à l'expérience de Stern et Gerlach et à la résonance magnétique; J. Phys. Radium 11 (1950) 255-265

Reference

A. Kastler: Quelques suggestions concernant la production optique et la détection optique d'une inégalité de population des niveaux de quantifigation spatiale des atomes. Application à l'expérience de Stern et Gerlach et à la résonance magnétique; J. Phys. Radium 11 (1950) 255-265

-

MASER — The forerunner of laser

MÉZER – A lézer elődje

Military developments in World War II brought significant advances in microwave and radio wave technology, and boosted academic research in the field.

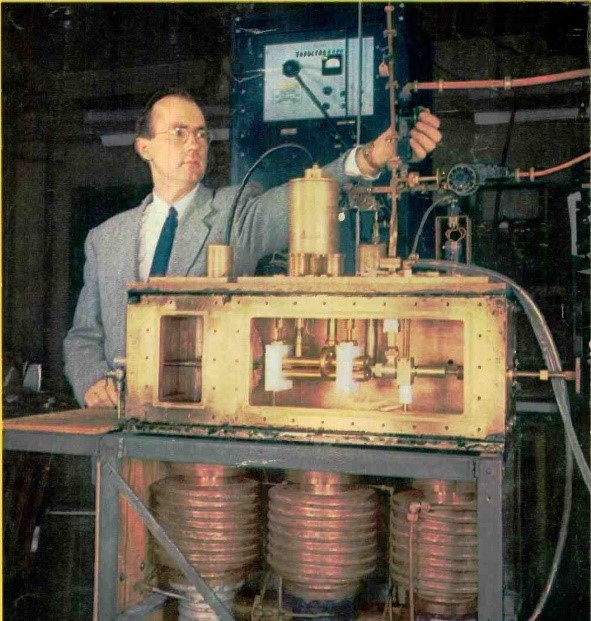

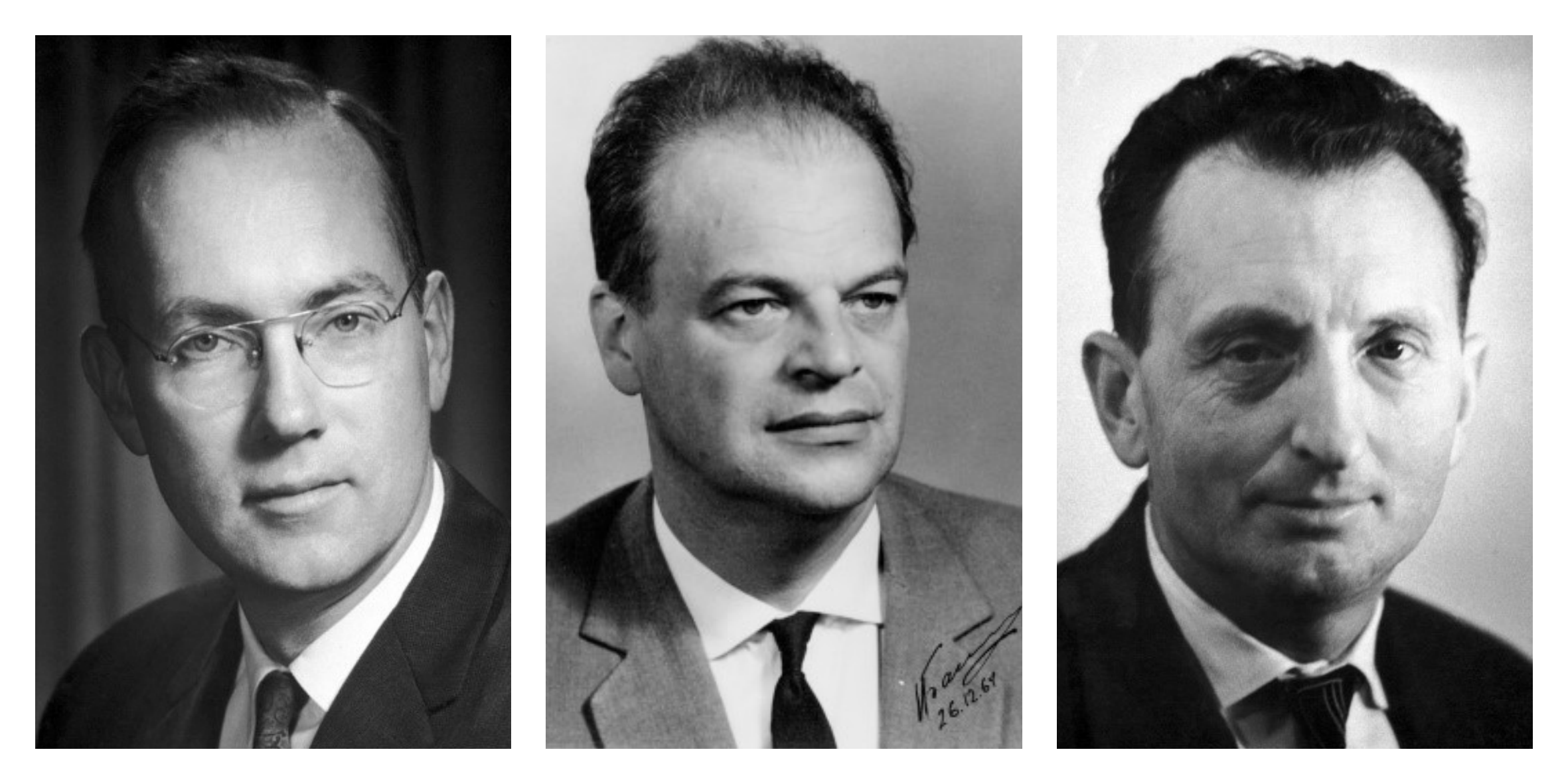

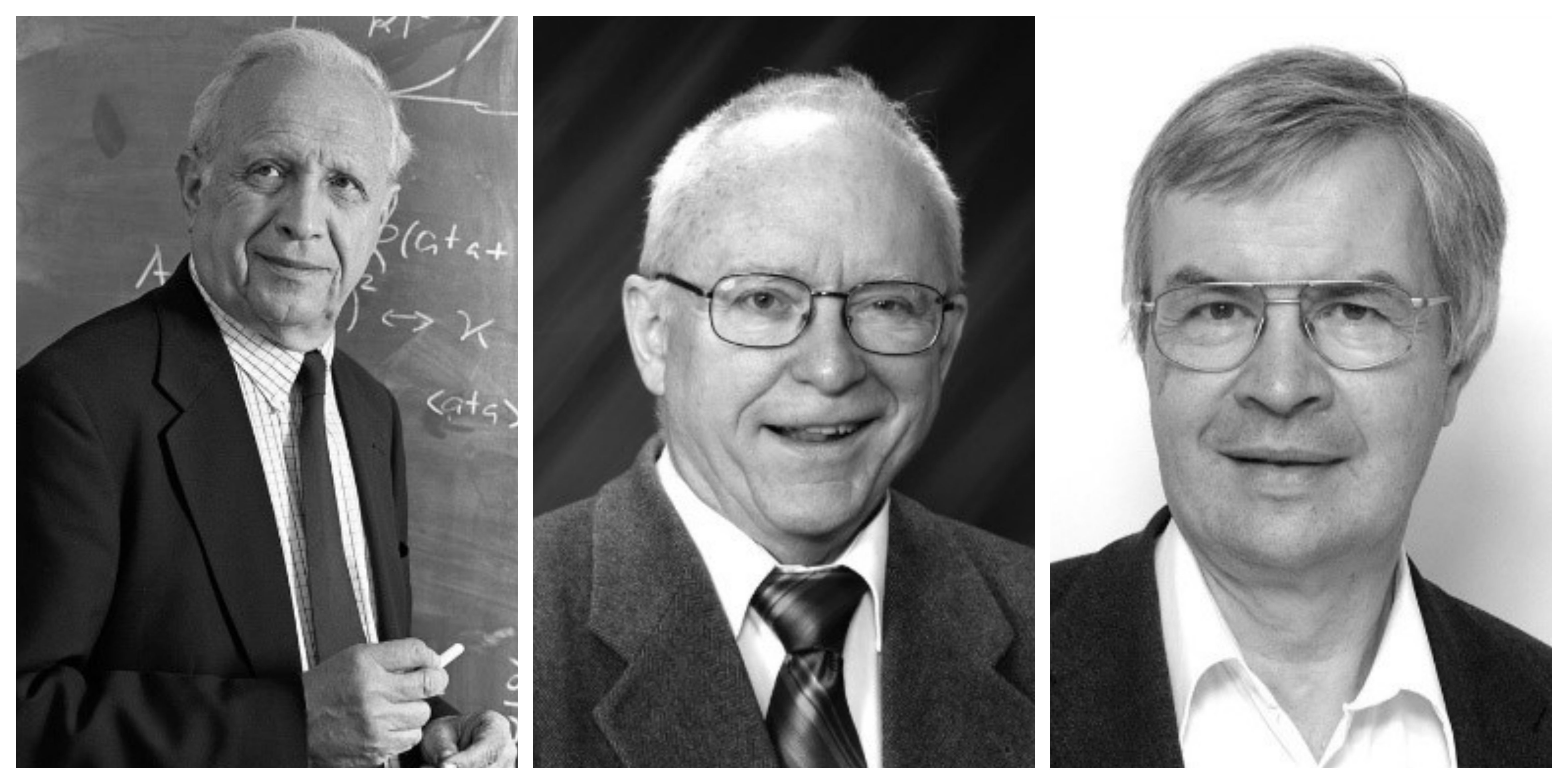

The theory of stimulated emission and the method of optical pumping were applied simultaneously but independently by Charles H. Townes (USA), as well as by Nikolai G. Basov and Alexander M. Prokhorov (USSR) to stimulate gaseous ammonia in a suitably sized resonator cavity to emit coherent photons in quantities exceeding those of exciting photons. This radiation occurred in the microwave spectrum, wherefore they named their device microwave resonator and then MASER, which is the acronym of Microwave Amplification by Stimulation Emission of Radiation.

These research activities paved the way for the development of devices suitable for practical applications, including masers emitting in the infrared and visible spectrum, i.e. lasers. Their efforts were rewarded with a shared Nobel Prize in 1964.

A második világháború haditechnikája a mikro- és rádióhullámok területén komoly technológiai fejlődést hozott, lendületet adva ezen a területen az akadémiai kutatásoknak.

A kényszerített emisszió elméletét és az optikai pumpálás metódusát felhasználva egymással párhuzamosan, de egymástól függetlenül érte el Charles H. Townes (Amerikai Egyesült Államok), valamint Nyikolaj G. Baszov és Alekszandr M. Prohorov (Szovjetunió), hogy megfelelően méretezett üregbe zárt ammónia-gáz a gerjesztő fotonoknál nagyobb számban sugározzon ki koherens fotonokat. Ez a sugárzás a mikrohullámú tartományba esett, ezért eszközüket mikrohullámú rezonátornak, majd – a Microwave Amplification by Stimulation Emission of Radiation (mikrohullám erősítése sugárzás kényszerített emissziójával) rövidítéseként – mézernek nevezték el.

Kutatásaik megnyitották az utat a gyakorlatban is alkalmazható eszközök kifejlesztéséhez, beleértve az infravörös, és látható fény tartományban sugárzó mézerek, vagyis lézerek kifejlesztéséhez. Érdemeiket 1964-ben megosztott Nobel-díjjal ismerték el.

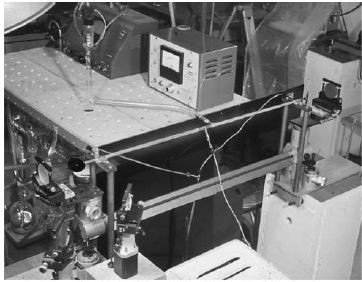

The ammonia maser at Columbia University and Charles H. Townes (1954).

The device emitted photons with a wavelength of a little over one centimetre, while its power was around 10 nW.A Columbia Egyetemen megépített ammónia-mézer és mellette Charles H. Townes (1954).

A készülék közelítőleg 10 nW teljesítménnyel sugárzott 1 cm-nél valamivel nagyobb hullámhosszúságú fotonokat. -

The first laser

Az első lézer

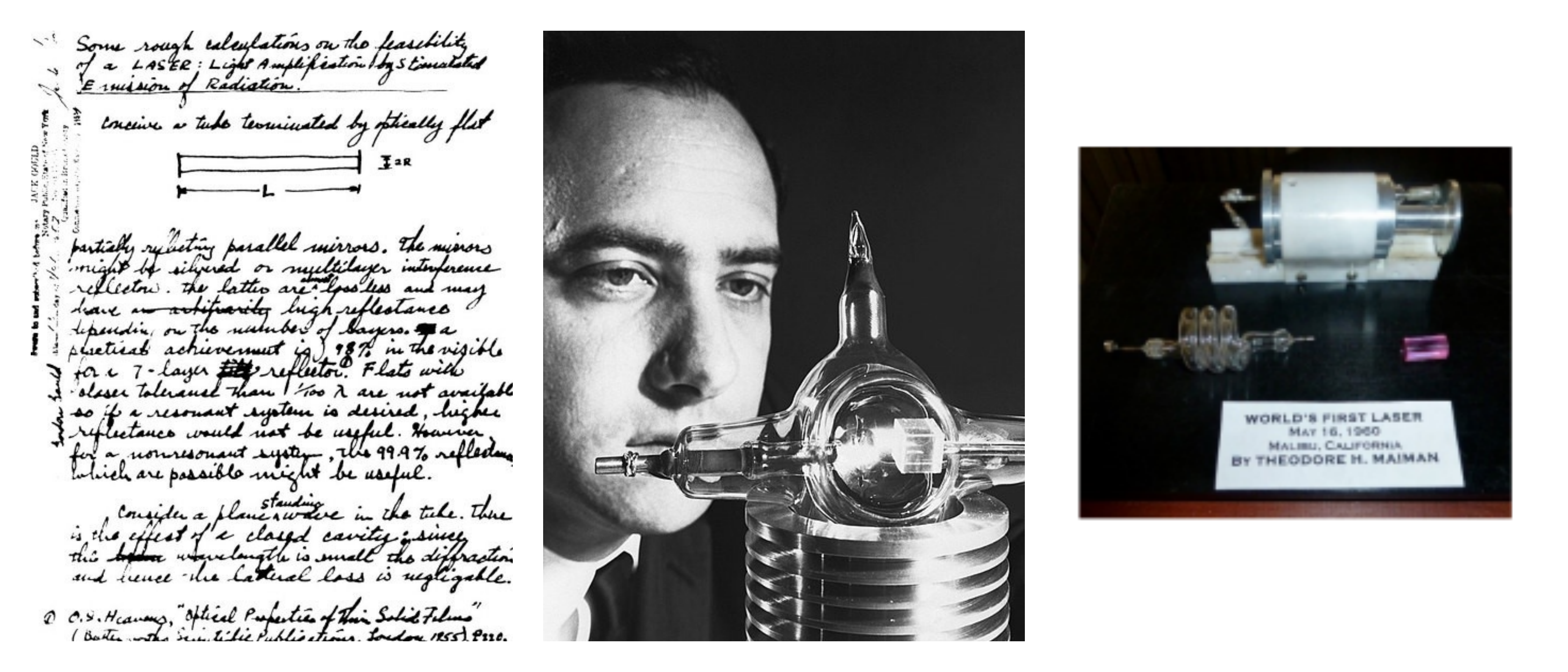

After the construction of masers emitting in the microwave range, research activities focused on the development of devices emitting coherent beams in the infrared and visible domain. These devices were named LASER, an acronym for Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation. The description of the building blocks of the laser – and the acronym itself – first appeared in Gordon Gould’s authenticated laboratory notes dated 13 November 1957.

The first working laser was fired by Theodore H. Maiman on 16 May 1960, and the new invention was demonstrated to the public at a press conference on 7 July 1960.

Maiman was hired by Hughes Aircraft Company in 1956 to lead the ruby maser redesign project for the US Army Signal Corps. Following the successful project, the company agreed on a $50,000 fund for his laser project, which started in 1959. Maiman developed the laser using a synthetic ruby crystal and used a pulsed, high-power quartz flashlamp to create the population inversion in the ruby crystal.A mikrohullámú tartományban sugárzó mézerek megalkotása után az infravörös és a látható tartományban koherens sugárzást kibocsátó eszközök kifejlesztésére irányultak kutatások. A Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation – fény erősítése sugárzás kényszerített emissziójával – rövidítéseként ezek az eszközök a lézer nevet kapták. A lézer szerkezeti felépítése és a betűszó Gordon Gould 1957. november 13-án hitelesített laborjegyzeteiben jelent meg.

Az első működő lézert Theodore H. Maiman indította be 1960. május 16-án, majd az új találmányt 1960. július 7-én mutatta be egy sajtótájékoztatón. Maiman 1956-ban állt alkalmazásba a Hughes Repülőgépgyárban, ahol az amerikai hadsereg híradós alakulatának megbízásából a rubinmézer továbbfejlesztésére irányuló munkálatokat vezette. A sikeres projekt nyomán a cég vállalta, hogy 50 000 dollárral támogatja Maiman 1959-ben megkezdett lézerfejlesztési kutatását. Maiman lézeréhez egy mesterségesen előállított rubinkristályt használt, amelyben impulzusüzemű, nagy teljesítményű kvarc villanólámpával idézte elő a populációinverziót.

Theodore H. Maiman, and the laser he built at Hughes Research Laboratories (1960) A Hughes Kutatólaboratóriumokban megépített lézer és megalkotója, Theodore H. Maiman (1960) -

Fibre lasers

Szállérezek

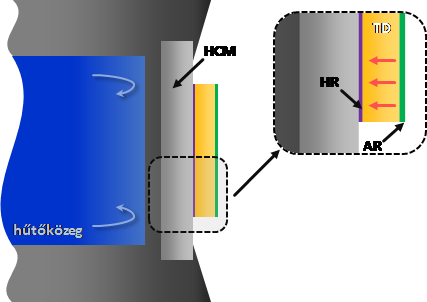

Some of the scientists working on the further development of lasers focused their efforts on finding materials to be used as active medium. The active medium consists of a host material and impurities distributed homogeneously within it. In addition to other materials, devices using doped glass as medium were introduced thanks to Elias Snitzer’s research efforts.

It had been known since the mid-19th century that in a thin glass fibre light is able to follow the curvatures of the fibre through a series of total internal reflections, i.e. optical fibres are able to guide light. This sparked the idea for the development of lasers using optical fibres as medium [1]. Three years later, optical amplification was achieved in a 1 m long fibre [2]. These developments have led to high quality fibre lasers currently used in a wide range of applications. In fibre lasers, the active medium is an optical fibre up to a few hundred metres in length and with a diameter ranging from a few micrometres to a few hundred micrometres (µm). A long medium has excellent pumping efficiency and high amplification performance, while heat effects are negligible due to the small diameter. The different optical elements can be inserted into the optical fibres, wherefore the laser beam can be produced wherever it is needed, and propagation mid-air can be avoided. On the other hand, fibre lasers have limited performance due to nonlinear phenomena caused by the geometry of the fibres as well as optical damage.

A lézerek továbbfejlesztésének egyik iránya a médiumként – vagyis a lézerműködés aktív közegeként – használható anyagok körével foglalkozott. Az aktív közeg valamilyen hordozóanyagból és ebben eloszlatott adalékanyagból áll. Több más anyag mellett Elias Snitzer fejlesztéseként megjelentek a médiumként adalékolt üveget használó készülékek is.

Már a XIX. század közepétől ismert volt, hogy egy vékony üvegszálban a fény sorozatos teljes visszaverődések folytán követi az üvegszál görbületeit, vagyis az üvegszál képes a fényt vezetni. Ezt felhasználva alakult ki a médiumként üvegszálat alkalmazó lézer koncepciója [1]. Három évvel később már 1 m hosszúságú szálban hoztak létre optikai erősítést [2]. E fejlesztések vezettek el a ma már széles körben alkalmazott, magas minőségű szállézerekhez. A szállézerek aktív közege egy optikai szál, amelynek hossza akár néhány száz méter is lehet, az átmérője pedig néhány µm-től a néhány száz µm-ig terjedhet. A hosszú médium igen hatékonyan pumpálható és vele nagy erősítés érhető el, a kis keresztmetszet pedig elhanyagolhatóvá teszi a hőhatásokat. A fényvezető szálba beépíthetők a különböző optikai elemek, így a lézersugár ott állítható elő, ahol arra szükség van, ezáltal elkerülhető a nyaláb levegőben való vezetése. A szállézerekkel elérhető teljesítmény a geometriai adottságok miatt fellépő nemlineáris jelenségek és az erőteljesebb optikai roncsolódás miatt korlátozott.

Elias Snitzer working at American Optical in 1964 Elias Snitzer munka közben az American Optical cégnél 1964-ben

Referenciák

[1] E. Snitzer: Optical Maser Action of Nd +3 in a Barium Crown Glass; Physical Review Letters 7 (1961) 12

[2] C. J. Koester, E. Snitzer: Amplification in a Fiber Laser; Applied Optics 3 (1964) 10, 1182-1186

References

[1] E. Snitzer: Optical Maser Action of Nd +3 in a Barium Crown Glass; Physical Review Letters 7 (1961) 12

[2] C. J. Koester, E. Snitzer: Amplification in a Fiber Laser; Applied Optics 3 (1964) 10, 1182-1186

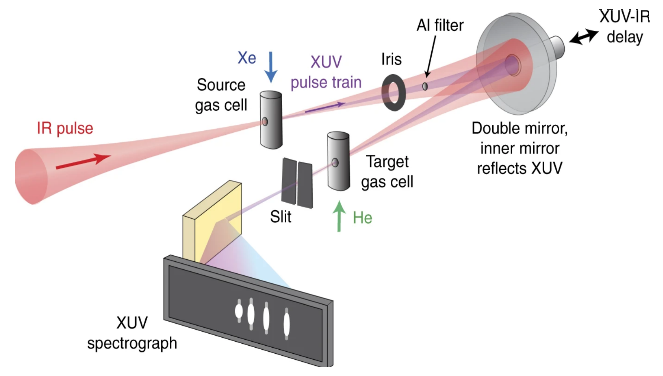

Nonlinear optics

Nemlineáris optika

When a light beam reaches the boundary of a new medium, part of the beam is reflected, part is transmitted and part is absorbed by the new medium. In the case of low intensity light beams this usually happens without any change in the wavelength of the light beam: incident, reflected, transmitted and absorbed light beams have identical wavelengths.

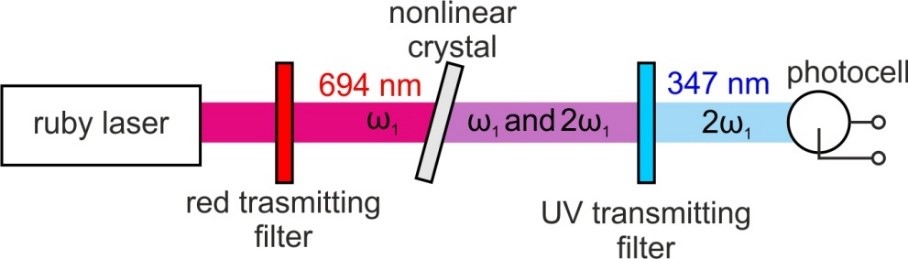

Nonlinear optical effects were first reported by Peter A. Franken and co-workers in 1961 [1]: in their experiments they focused the beam of the newly developed ruby laser (λ=694.2 nm) into a quartz crystal and found that the wavelength of the light leaving the crystal was shorter than that of the incident light. The high intensity laser beam used in the experiments produced a new, coherent beam in the ultraviolet range (λ=347.1 nm) upon interaction with the quartz crystal.

One year later, Robert W. Terhune and co-workers observed third harmonic generation in calcite crystal.

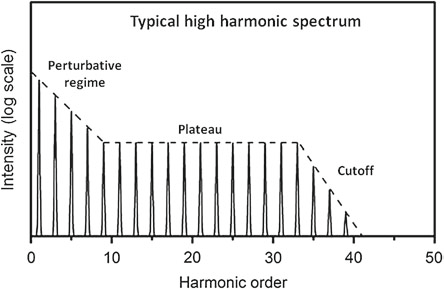

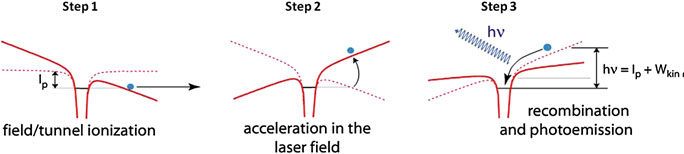

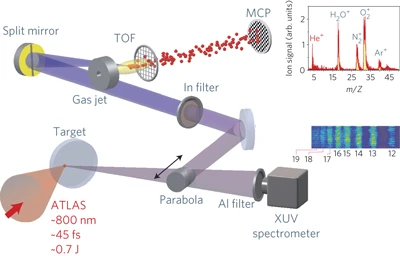

The attosecond light pulses of ELI-ALPS are high harmonics in the extreme ultraviolet (XUV) range produced via nonlinear processes from infrared laser pulses.

Új közeg határához érve a fénysugár részben visszaverődik, részben behatol az új közegbe. Alacsony intenzitású fénynyalábok esetén ez rendszerint a fény hullámhosszának megváltozása nélkül történik: a beérkező, a visszavert és az új közegbe hatoló fény hullámhossza megegyezik.

Első alkalommal 1961-ben Peter A. Franken és munkatársai számoltak be nemlineáris optikai effektusról [1]: kísérleteikben az akkoriban felfedezett rubinlézerrel (λ=694,2 nm) kvarckristályon világítottak keresztül, és azt tapasztalták, hogy a kristályt az eredetinél rövidebb hullámhosszúságú fénysugár hagyta el. A kísérletekben használt nagyintenzitású lézersugár a kvarckristállyal való kölcsönhatásakor új, koherens nyalábot hozott létre az ultraibolya tartományban (λ=347,1 nm).

Egy évvel később Robert W. Terhune és munkatársai kalcitkristályban mutatták ki harmadik felharmonikus keltését.

Az ELI-ALPS attoszekundumos fényimpulzusai infravörös lézerimpulzusokból nemlineáris folyamatok során előállított, az extrém ultraibolya tartományba eső magasrendű felharmonikusok.

A Franken és munkatársai által másodrendű harmonikus keltéséhez használt

kísérleti elrendezés sematikus rajza

(http://www.physics.ttk.pte.hu/files/TAMOP/FJ_Nonlinear_Optics/1_introduction.html)Scheme of the second-harmonic generation experiment of Franken and co-workers

(http://www.physics.ttk.pte.hu/files/TAMOP/FJ_Nonlinear_Optics/1_introduction.html)

Referenciák

[1] P. A. Franken, A. E. Hill, C. W. Peters, and G. Weinreich: Generation of Optical Harmonics; Physical Review Letters 7 (1961) 118

[2] R. W. Terhune, P. D. Maker, and C. M. Savage: Optical Harmonic Generation in Calcite; Physical Review Letters 8 (1964) 404

References

[1] P. A. Franken, A. E. Hill, C. W. Peters, and G. Weinreich: Generation of Optical Harmonics; Physical Review Letters 7 (1961) 118

[2] R. W. Terhune, P. D. Maker, and C. M. Savage: Optical Harmonic Generation in Calcite; Physical Review Letters 8 (1964) 404

The semiconductor laser

A félvezető lézer

The uniqueness of semiconductor lasers – also known as diode lasers – lies in their small size and suitability to be pumped by electrical current. A further advantage is that they can be cost-efficiently mass produced.

After the demonstration of the first operational laser in 1960, one direction of development was to study materials that can potentially be used as gain medium.

The first semiconductor laser was constructed in the laboratory of General Electric in the early 1960s, only few years ahead of the researchers of IBM. The prototype comprised merely one n-type (excess negative charge) and one p-type (excess positive charge) semiconductor layer, and the laser beam was produced in the narrow junction between these two layers.

A félvezető lézerek — más néven dióda-lézerek — különlegessége a kis méret és az elektromos árammal való vezérelhetőség. További előnyük, hogy költséghatékonyan, tömeggyártásban készíthetők.

Az első működő lézer 1960-as bemutatása után az egyik fejlesztési irány a médiumként alkalmazható anyagok kutatása volt.

Az első félvezető lézert a General Electric laborjában készítették az 1960-as évek elején, csupán néhány héttel megelőzve az IBM kutatóit. A prototípus mindössze egy n-típusú (elektrontöbblettel rendelkező) és egy p-típusú (elektronhiánnyal rendelkező) félvezető rétegből állt, és a lézersugár pedig e két réteg közötti vékony határrétegben alakult ki.

If the two ends of the diode (anode and cathode) are connected with a voltage source, charge transfer starts between the two semiconductor layers. During the recombination of the electron and hole pairs, when the electron moves from a higher to a lower energy level, the excess energy is released in the form of photons.

At low current densities the process is not self-sustaining: light is emitted from the junction without amplification. This is spontaneous emission, which forms the operating principle of ordinary LEDs (light emitting diodes).

At higher current densities, a self-sustaining process starts (stimulated emission). If the end planes of the semiconductor crystal are polished to be perfectly parallel to each other, they work as a mirror resonator and reinforce the process. Then high intensity, coherent and monochromatic light is emitted from the junction.

A dióda két vége (az anód és a katód) közé feszültséget kapcsolva a két félvezető réteg között megindul a töltésáramlás. Az elektron és lyuk párok rekombinációs folyamata során, amikor az elektron magasabb energiaszintről alacsonyabb energiaszintre kerül, a többletenergia foton formájában távozik.

Kis áramerősség mellett a folyamat még nem önfenntartó: a fény erősödés nélkül jön ki a határrétegből. Ez a spontán emisszió, így működik a hétköznapi LED (light emitting diode).

Nagyobb áramerősség mellett beindul egy önfenntartó folyamat (kényszerített emisszió). Ha a félvezető kristály véglapjait párhuzamosra polírozzuk, azok tükörrezonátorként működnek és erősítik a folyamatot. Ekkor nagy intenzitású, koherens és monokromatikus lézerfény lép ki a határrétegből.

The colour of the laser light depends on the chosen semiconductor material. For example, when InGaN is used as semiconductor material, the emitted light is blue or green, but when InGaAs is used, infrared light leaves the laser. The active gain mediums of semiconductor lasers are typically the combinations of elements in the third group (e.g. Al, Ga, In) and the fifth group (e.g. N, P, As, Sb) of the periodic table. The medium of the first semiconductor laser built in 1962 was GaAs, and the wavelength of the emitted light was in the infrared spectrum. Present-day diode lasers are much more sophisticated, and generate light in the UV, the visible and the infrared ranges alike.

Although early laser diodes were produced a few years after the demonstration of the first laser, the semiconductor industry had to undergo significant development to improve the reliability, increase the life and reduce the production costs of these devices, and thus to allow them to become part of our lives. By today, diode lasers have become the most frequently used lasers and can be found almost everywhere: in barcode scanners, remote controllers, telecommunication devices, etc. They are also widely used to pump solid-state lasers.

A lézerfény színe a választott félvezető anyagtól függ. Például InGaN félvezető esetén kék vagy zöld lézerfény hozható létre, InGaAs félvezető alkalmazásakor pedig infravörös fény keletkezik. A félvezető lézerek médiumait jellemzően a periódusos rendszer harmadik (pl. Al, Ga, In) és ötödik csoportjába (pl. N, P, As, Sb) tartozó elemek kombinációi alkotják. Az 1962-ben előállított első félvezető lézer médiuma GaAs volt, a kibocsátott fény hullámhossza pedig az infravörös tartományba esett. A mai dióda-lézerek már jóval kifinomultabb szerkezetűek, és az UV, a látható és az infravörös tartományban állítanak elő fényt.

Bár a korai lézerdiódák már az első lézer felfedezését követően néhány évvel megépültek, a félvezető ipar jelentős fejlődésére volt szükség ahhoz, hogy ezen eszközök megbízhatóvá, hosszú élettartamúvá, olcsón előállíthatóvá, és így mindennapi életünk részeivé váljanak. Manapság már ez a leggyakrabban használt lézertípus, szinte mindenhol megtalálható: pl. vonalkód-olvasókban, távirányítókban, telekommunikációs eszközökben, valamint széles körben használják őket szilárdtest-lézerek pumpálására.

Ábrák

https://circuitglobe.com/laser-diode.html

Figures

https://circuitglobe.com/laser-diode.html

The first Hungarian laser

Az első magyar lézer

Soon after T. H. Maiman’s ruby laser (1960) and the first helium-neon gas laser (1961) implemented by A. Javan, W. R. Bennett and D. R. Herriott in 1963, physicists at the Central Research Institute for Physics (KFKI) József Bakos, László Csillag, Károly Kántor and Péter Varga built the first Hungarian He-Ne laser [1, 2].

In the early 1960s, this was an exceptionally great and important achievement, because behind the iron curtain and under the pressure of trade sanctions this field of experimental physics could only be studied with self-developed devices. For around two decades, optical research and the development of laser applications in Hungary was made possible by lasers built at KFKI and other domestic places of research, e.g. Szeged.

Röviddel T. H. Maiman rubinlézere (1960) és az A. Javan, W. R. Bennett és D. R. Herriott által megvalósított első hélium-neon gázlézer (1961) után, 1963-ban a Központi Fizikai Kutatóintézet fizikusai, Bakos József, Csillag László, Kántor Károly és Varga Péter megépítették az első magyar hélium-neon lézert [1, 2].

Az 1960-as évek elején ez különösen nagy és fontos teljesítmény volt, hiszen a vasfüggöny mögött, kereskedelmi embargótól sújtva csak saját fejlesztésű eszközökkel lehetett művelni a kísérleti fizikának ezt a területét. Mintegy két évtizeden keresztül a KFKI-ban és más hazai kutatóhelyeken (pl. Szegeden) gyártott lézerek tették lehetővé az optikai kutatások és lézeralkalmazások fejlődését Magyarországon.

The design of the first Hungarian laser was not identical with that of the first He-Ne laser built by Javan, Bennett and Herriott. With small, but important changes the KFKI team was able to make the generated laser beam linearly polarized. Instead of dielectric plane mirrors the researchers used silver spherical mirrors inside the resonator, which made alignment easier and allowed for the laser to be operated not only at 1.15 µm, but also at a wavelength of 2.39 µm and 3.39 µm, respectively. [3, 4]

Az első magyar lézer felépítése nem azonos a Javan, Bennett és Herriott által először épített hélium-neon lézerével. A KFKI csapata apró, de fontos változtatásokkal elérte, hogy a keltett lézerfény lineárisan polarizált legyen. Dielektrikum síktükrök helyett ezüst gömbtükröket használtak a rezonátorban, ami megkönnyítette a beállítást, és azt is lehetővé tette, hogy a lézer nemcsak 1,15 µm, hanem 2,39 µm és 3,39 µm hullámhosszakon is működjön. [3, 4]

By the 1980s, several Hungarian research groups had devoted their efforts to study the medical, industrial, environmental and other possible applications of lasers.

Az 1980-as évekre több kutatócsoport is foglalkozott Magyarországon a lézerek orvosi, ipari, környezetvédelmi és egyéb lehetséges felhasználásaival.

Referencia

[1] Magyar laser a Központi Fizikai Kutató Intézetben; Magyar Nemzet 1963. dec. 15.

[2] Bakos J., Csillag L., Kántor K., Varga P.: Ezüsttükrös nagyfrekvenciás gerjesztésű He-Ne laser; KFKI Közl. 13 (1965), 195–197.

[3] Donkó Z.: Gázlézerek és gázkisülések; Fizikai Szemle 2005/7. 240.o.

[4] Csillag L.: Ötven éves az első magyar lézer; Fizikai Szemle 2013/6. 197.o.

References

[1] Magyar laser a Központi Fizikai Kutató Intézetben; Magyar Nemzet 1963. dec. 15.

[2] Bakos J., Csillag L., Kántor K., Varga P.: Ezüsttükrös nagyfrekvenciás gerjesztésű He-Ne laser; KFKI Közl. 13 (1965), 195–197.

[3] Donkó Z.: Gázlézerek és gázkisülések; Fizikai Szemle 2005/7. 240.o.

[4] Csillag L.: Ötven éves az első magyar lézer; Fizikai Szemle 2013/6. 197.o.

The 1964 Nobel Prize in Physics

Az 1964. évi fizikai Nobel-díj

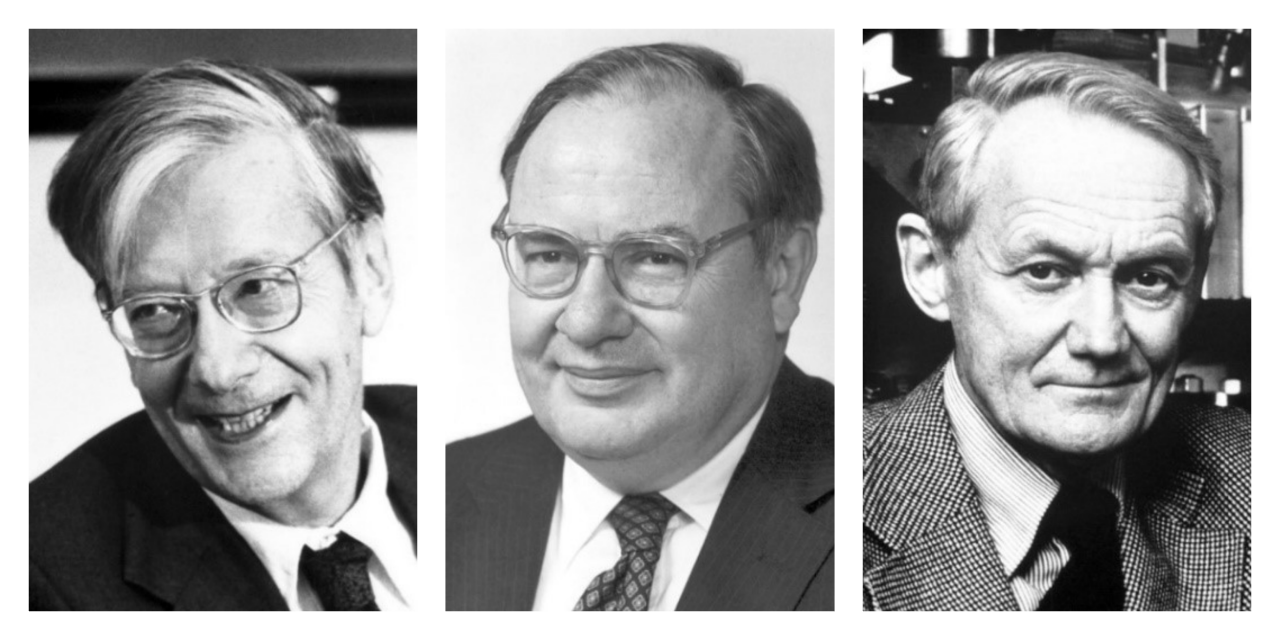

In 1964, the Nobel Prize in physics was awarded for fundamental work in the field of quantum electronics, which subsequently led to the construction of masers and lasers. The Prize was divided among Charles H. Townes, Nikolai G. Basov> and Alexander M. Prokhorov.

Az 1964-es fizikai Nobel-díjat a mézerek és lézerek megvalósításához vezető kvantumelektronikai alapkutatásokért ítélték oda. Az elismerést Charles H. Townes, Nyikolaj G. Baszov és Alekszandr M. Prohorov kapta megosztva.

According to the process of stimulated emission described by Einstein in 1917, the energy bunch – photon – interacting with the atom may stimulate the emission of another photon, identical with the original photon in terms of energy while returning to a lower energy state. This process creates the theoretical possibility for the amplification of radiation.

However, special conditions are required to observe and apply this process for practical purposes. Under normal conditions, the overwhelming majority of atoms in matter are in the ground state, wherefore the energy of incident photons excites atoms to higher energy states, and only a small fraction of electrons undergoes stimulated emission. Consequently, the ratio of atoms in the ground and excited state must be reversed: we need matter in which excited atoms prevail, i.e. where excitation is no longer induced by the irradiated photons. In this case incident photons force the relaxing atoms to emit identical photons, and they produce a large amount of coherent photons.

This means that the first step towards the implementation of radiation amplifying devices, i.e. masers (Microwave Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation) and lasers (Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation) was the creation of population inversion.

The first papers on masers were published in 1954 as a result of investigations carried out simultaneously but independently by Charles H. Townes ad co-workers at Columbia University in New York, and by a team led by Nikolai G. Basov and Alexander M. Prokhorov at the Lebedev Institute in Moscow. In the first maser (1954) stimulated emission occurred in ammonium gas. The subsequent years saw the birth of various maser types that applied ruby, hydrogen or rubidium as active medium. The accuracy of atomic clocks is maintained by hydrogen masers; to keep noise level to the minimum, masers are used as microwave amplifiers in radio telescopes, and masers also play a role in astrophysical research.

The history of the optical maser, i.e. the laser dates back to 1958, when Arthur L. Schawlow and Townes, as well as scientists at the Lebedev Institute began to investigate how the operating principle of the maser can be used in the optical range. Two years later they constructed the first operational laser.

The 100,000-fold growth in frequency from the microwave range to the region of visible light changes the operating conditions to a degree that justifies lasers to be regarded as a completely new invention. In order to achieve a high energy density required for the dominance of stimulated emissions, the active medium must be placed between two mirrors that force light to traverse the medium many times. During this process, a cascade of stimulated emissions continues as long as all atoms have released their energy. For the result of the process it is essential that the stimulated and the stimulating radiation have the same phase and frequency. Due to resonance, waves coming from all parts of the active medium are combined to form a single, strong beam. The laser emits a so-called coherent light in contrast with other light sources where light is the result of atoms radiating independently of one another.

The inventors of the laser provided mankind with a tool the applications of which have multiplied in the past decades: it has gained widespread exploitation not only in science, but also in the industry, medicine, cosmetics, in micro- and nanotechnology, military technology, and we see more and more everyday devices that operate with lasers.

A kényszerített emisszió Einstein által 1917-ben leírt folyamata szerint az atommal kölcsönhatásba kerülő energiacsomag – foton – hatására az atom gerjesztett elektronja alacsonyabb energiaszintre való visszatérés közben az eredetivel azonos energiájú fotont bocsáthat ki. Ez a folyamat elméleti lehetőséget teremt sugárzás erősítésére.

Ahhoz, hogy ez a folyamat megfigyelhető, illetve gyakorlati célra felhasználható legyen, különleges körülmények szükségesek. Szokásos viszonyok között az anyaghalmazokban az atomok túlnyomó többsége alapállapotú, ezért a besugárzott fotonok energiája főleg ezen atomok gerjesztését okozza, és csak elenyésző hányadban hozza létre a kényszerített emissziót. El kell tehát érni, hogy az alap- és gerjesztett állapotú atomok aránya megforduljon: olyan anyaghalmazra van szükség, amelyben a gerjesztett atomok vannak többségben, vagyis a gerjesztést már nem a besugárzott fotonoknak kell elvégezni. Ilyenkor a besugárzott fotonok önmagukkal azonos fotonok kisugárzására kényszerítik a relaxálódó atomokat, nagy mennyiségű koherens fotont eredményezve.

A sugárzást erősítő eszközök – mézerek (Microwave Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation) és lézerek (Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation) – elkészítéséhez vezető út első lépése tehát a populációinverzió létrehozása.

A mézerrel kapcsolatos első közlemények 1954-ben jelentek meg, amikor egymástól függetlenül, de egy időben a New York-i Columbia Egyetemen Charles H. Townes és munkatársai, valamint a moszkvai Lebegyev Intézetben Nyikolaj G. Baszov és Alekszandr M. Prohorov ezirányú vizsgálatokat végeztek. Az első mézerben (1954) ammónium-gázban történt a kényszerített emisszió. Az ezt követő években számos, különböző típusú mézer készült: rubin, hidrogén, rubídium is megjelent médiumként. Az atomórák pontosságát hidrogénmézerek biztosítják, az alacsony zajszint érdekében mézereket használnak rádiótávcsövek mikrohullámú erősítőjeként, és asztrofizikai kutatásokban is szerepet játszanak a mézerek.

Az optikai mézer, azaz a lézer története 1958-ra nyúlik vissza, amikor Arthur L. Schawlow és Townes, valamint a Lebegyev Intézet munkatársai is vizsgálni kezdték, miként alkalmazható a mézer működési elve az optikai tartományban. Két évvel később megalkották az első működő lézert.

A mikrohullámú tartomány és a látható fény tartománya közötti százezerszeres frekvencianövekedés olyan változásokat eredményez a működési feltételekben, hogy a lézer teljesen új találmánynak tekinthető. Ahhoz, hogy a kényszerített emisszió dominanciájához szükséges magas energiasűrűséget elérjük, az aktív anyagot két tükör közé kell helyezni, amelyek arra kényszerítik a fényt, hogy sokszor áthaladjon az anyagon. E folyamat során a kényszerített sugárzás lavinaszerűen nő mindaddig, amíg az összes atom le nem adta az energiáját. A folyamat eredménye szempontjából szükséges, hogy a stimulált és a stimuláló sugárzás azonos fázisú és frekvenciájú legyen. A rezonanciának köszönhetően az aktív közeg minden részéből összeadódnak a hullámok, és egyetlen erős nyalábot hoznak létre. A lézer úgynevezett koherens fényt bocsát ki, ellentétben más fényforrásokkal, amelyeknek a fényét az egyes atomok egymástól függetlenül lejátszódó folyamatai eredményezik.

A lézer feltalálói olyan eszközt adtak az emberiség kezébe, amelynek alkalmazási területei az elmúlt évtizedek során megsokszorozódtak: a tudományos kutatások mellett használatuk elterjedt az iparban, alkalmazásuk ismert a gyógyászatban, a kozmetikában, a mikro- és nanotechnológiában, harcászatban és mindennapi életünkben is egyre több olyan eszköz jelenik meg, amelyben lézer működik.

Dye lasers

Festéklézerek

Soon after the first laser was presented (1960, Theodore Maiman), scientists proved that many different materials are capable of laser light production. The birth of the ruby laser was followed by the construction of solid-state lasers, such as the neodymium:glass laser, the YAG crystal laser or the gallium arsenide diode laser, the first laser with a semiconductor as active medium. Within six months from the appearance of the ruby laser, scientists built the first gas laser, which used a gaseous mixture of helium and neon as an amplifying medium. The next milestone in laser development was the introduction of the carbon dioxide laser and the argon ion laser, which was the first laser capable of operating at several wavelengths (i.e. in several colours).

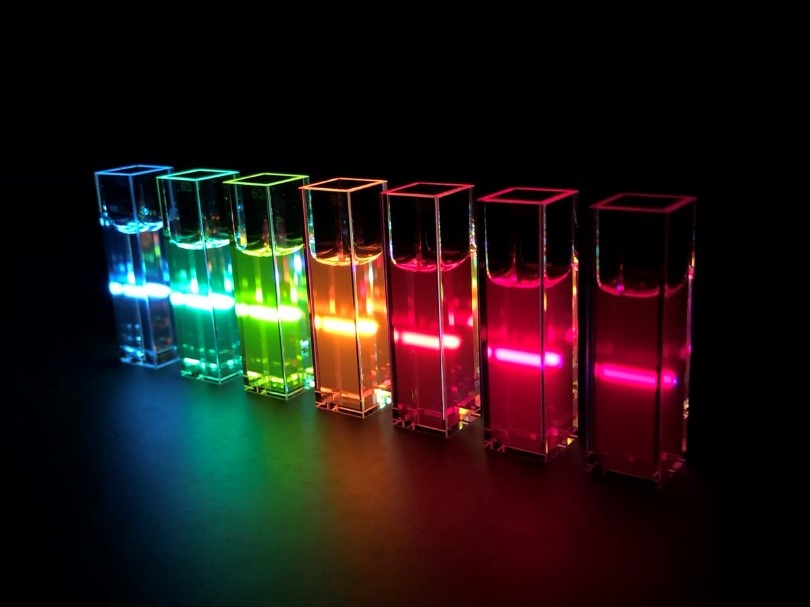

The first laser with a liquid amplifying medium was developed in 1966 almost concurrently, but independently by Peter P. Sorokin [1], an American physicist of Russian descent and his German counterpart, Fritz P. Schäfer [2]. They used organic dye solutions as optical amplifying medium which they excited in glass cuvettes with other lasers or a flashlamp. Acting as a resonator, the walls of the cuvette provided feedback to the amplifying medium.

Az első lézer bemutatását (1960, Theodore Maiman) követően a tudományos kutatások rövid időn belül különböző anyagok egész soráról bizonyították be, hogy alkalmasak lézerműködésre. A rubinlézer után olyan szilárdtest alapú lézereket állítottak elő, mint a neodímium-üveg lézer, a YAG-kristály lézer valamint az első félvezető anyagú gallium-arzenid dióda-lézert. A rubinlézer után alig fél évvel építették meg az első gázlézert, ami hélium és neon gázkeverék erősítő közegén alapult. Ezt a szén-dioxid és az első több hullámhosszon (azaz több színben) is működni képes argon-ion lézer követte.

Az első folyadék erősítő közegű lézert 1966-ban egymástól függetlenül, de szinte egyidőben Peter P. Sorokin [1] orosz származású amerikai és Fritz P. Schäfer [2] német fizikus fejlesztette ki. Optikai erősítő közegként szerves festékoldatokat használtak, amelyeket egy üveg küvettában más lézerekkel vagy villanólámpával gerjesztettek. A küvetta falai rezonátorként működve biztosították az erősítő közegbe való visszacsatolást.

Fluorescent light of various dyes. [3] Különböző típusú festékek floureszcens fénye. [3]

An important property of these organic, often toxic dye solutions is that they are capable of optical amplification in a very broad wavelength range. For example, the rhodamine 6G dye can be used as a lasing medium from the red through the orange to the greenish yellow spectrum. Using different dyes, the entire spectral range (from ultraviolet to red), as well as the ultraviolet and the near infrared spectra can be accessed. This property makes them suitable for the production of wavelength tuneable lasers (or narrowband lasers in case a strong wavelength selection mechanism is used). Another advantage of a broad spectral range is that such lasers are outstanding for the generation of ultrashort light pulses, wherefore they enjoyed priority for ultrashort pulse lasers up to the early 1990s. Dye lasers were able to reach a pulse duration of 27 fs (femtosecond = 10

-15 s) already in the middle of the 1980s, which could then be further reduced to 6 fs by post-compression. This time duration is shorter than the time required for the fastest chemical reaction and equals the time an electron travels nearly 40 circular orbits in the hydrogen atom.

Ezeknek a gyakran toxikus, szerves festékoldatoknak fontos tulajdonsága, hogy nagyon széles hullámhossztartományban képesek optikai erősítésre. A rodamin 6G típusú festékkel például a pirostól a narancson át a zöldessárga színig lehet lézerműködést produkálni. Különböző festékekkel pedig az egész látható tartomány (az ibolyától a vörösig) valamint az ultraibolya és közeli infravörös tartomány is elérhető. E tulajdonságuk alkalmassá teszi őket hullámhossz szerint hangolható (és erős hullámhossz-szelekció esetén keskenysávú) lézerek gyártására. A széles spektrális tartomány másik nagy előnye, hogy kiválóan alkalmasak rövid fényimpulzusok generálására, ezért a rövid impulzusú lézerek területén egészen a 90-es évek elejéig vezető szerepet töltöttek be. A festéklézerek segítségével már a 80-as évek közepén 27 fs (femtoszekundum, 10

-15 s) rövid impulzusokat tudtak generálni, amit később utólagos kompresszióval sikerült 6 fs-ra rövidíteni. Ez az időtartam rövidebb, mint a leggyorsabb kémiai reakcióhoz szükséges idő és valamennyivel rövidebb, mint amennyi idő alatt az elektron a hidrogénatomban 40 körpályát megtesz.

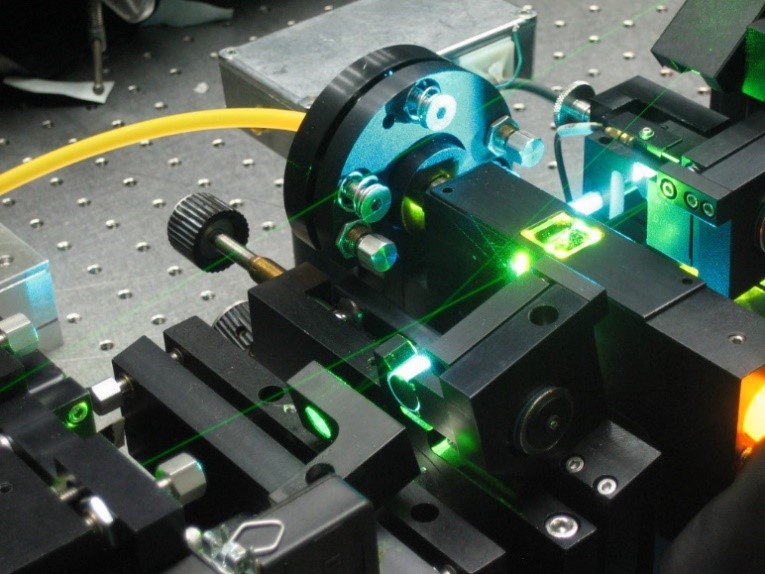

When excited with a blue argon ion pumping laser, rhodamine, an orange fluorescent dye, generates a laser beam in the green spectral region, which is then fed back into the amplifying medium with a ring resonator. [4] A csövekben narancssárgán fluoreszkáló rodamin festék a világoskék argon-ion pumpáló lézer hatására zöld színű lézersugárzást bocsát ki, amit egy gyűrűrezonátor segítségével vezetnek vissza az erősítőközegbe. [4]

Referencia

[1] P. P. Sorokin and J. R. Lankard: Stimulated emission observed from an organic dye, Chloro-aluminum Phtalocyanine; IBM J. Res. Develop. 10 (1966) 162

[2] F. P. Schafer, W. Schmidt, and J. Volze: Organic Dye solution laser; Appl. Phys. Letters 9 (1966) 306

[3] https://twitter.com/jonathangrimm/status/1062465313709678593

[4] https://www.flickr.com/photos/fatllama/42844367

References

[1] P. P. Sorokin and J. R. Lankard: Stimulated emission observed from an organic dye, Chloro-aluminum Phtalocyanine; IBM J. Res. Develop. 10 (1966) 162

[2] F. P. Schafer, W. Schmidt, and J. Volze: Organic Dye solution laser; Appl. Phys. Letters 9 (1966) 306

[3] https://twitter.com/jonathangrimm/status/1062465313709678593

[4] https://www.flickr.com/photos/fatllama/42844367

Erbium-doped fibre lasers

Erbium-adalékolt szálerősítők

One year after laser operation was first demonstrated (Theodore Maiman, 1960), the concept of using optical fibres as the active medium of lasers was developed (Elias Snitzer, 1961), and another three years later the completion of the first fibre laser was reported (Charles Koester, Elias Snitzer, 1964). The subsequent steps of technological development led to the construction of the first efficient fibre laser, the erbium-doped fibre laser (EDFA).

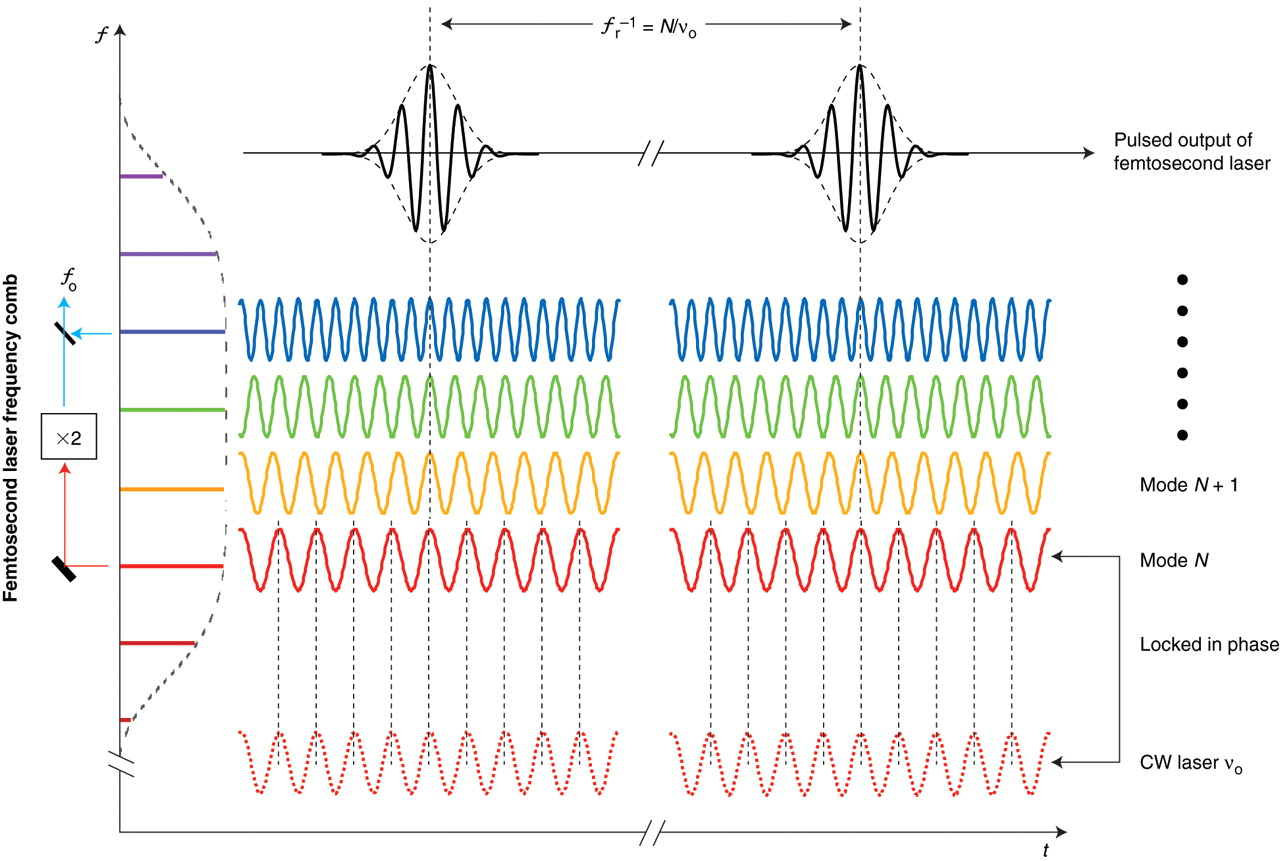

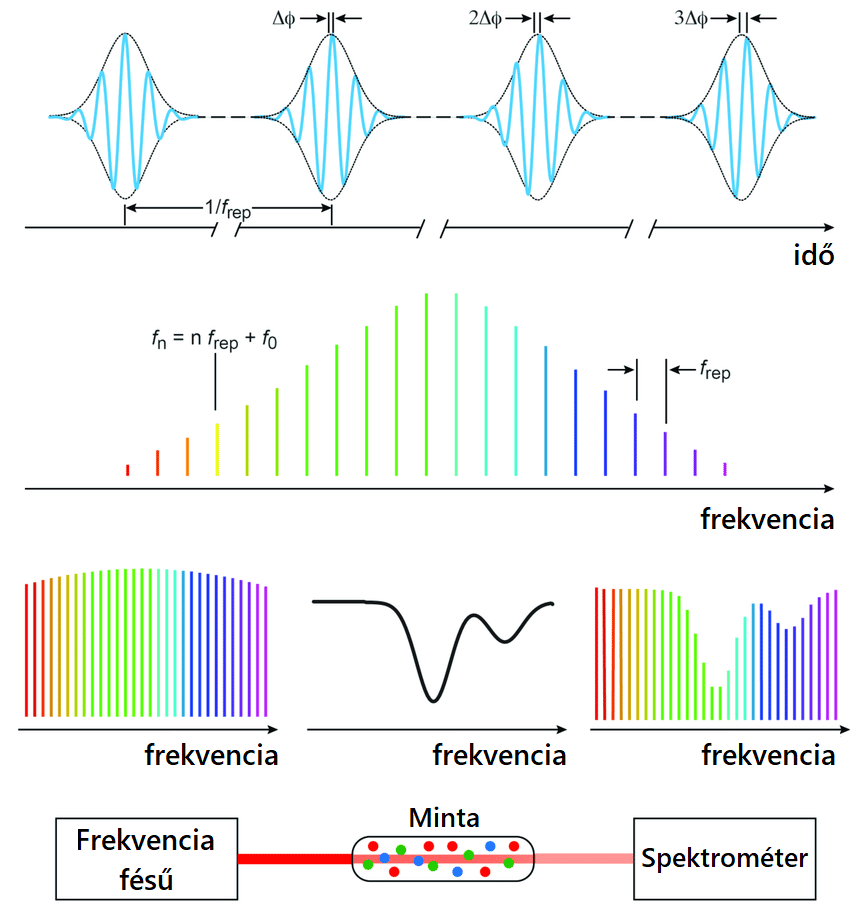

Erbium-doped fibre lasers [1, 2] are optical fibres whose core is doped with erbium ions, which allows for stimulated emission by a pumping light source having a suitable wavelength. The suitable wavelength is either 980 nm or 1480 nm, which is currently provided by semiconductor lasers. The operating principle of EDFAs is similar to that of ytterbium-doped fibre lasers invented earlier [3]. However, the operating wavelength is not around 1 μm, but around 1.5 μm, in the relatively broad spectral range of the so called telecommunication wavelength region [4]. This explains their significance: by being able to provide efficient optical amplification for the three (S, C and L) telecommunication bands [5,6], they have replaced electro-optical converters previously used for the regeneration of signals to be transmitted. At the same time, broadband operation makes this device suitable for use in short pulse fibre lasers too [7].

In 1970, continuous mode semiconductor lasers operating at room temperature and suitable for practical applications became commercially available, which contributed to the spread of fibre optic communication. Erbium-doped fibre lasers have been used in subsea optical transmission systems since 1996 [8]. In contrast with this, high power laser systems have adopted the enhanced versions of EDFAs: cladding pump and ytterbium co-doped fibres [9], as well as very-large-mode-area, erbium-doped fibre amplifiers [10].A lézerműködés első demonstrációja (Theodore Maiman, 1960) után egy évvel megszületett az a koncepció, amely szerint a lézer aktív közegeként optikai szálat lehet alkalmazni (Elias Snitzer, 1961), majd újabb három évvel később már az első szállézer elkészültét publikálták (Charles Koester, Elias Snitzer, 1964). Az ezt követő technológiai fejlesztések sora vezetett az első jól használható, hatékony szállézer, az erbium-adalékolt szállézer (erbium doped fibre laser, EDFA) megépítéséhez.

Az erbium-adalékolt szálerősítők [1, 2] olyan optikai szálak, amelyek magja erbiumionokkal szennyezett, lehetővé téve az indukált emissziót megfelelő hullámhosszú pumpáló fényforrás esetén. A megfelelő pumpáló hullámhossz 980 nm vagy 1480 nm, amelyet napjainkban félvezető lézerek szolgáltatnak. Az EDFA-k működési elve hasonlít a korábban megalkotott itterbium-adalékolt szálerősítőkéhez [3], ugyanakkor a működési hullámhossz nem az 1 μm körüli tartományban van, hanem az 1,5 μm körüli, úgynevezett telekommunikációs hullámhosszak környezetében, meglehetősen széles spektrális tartományban [4]. Jelentőségük ezért is növekedett meg kifejlesztésük után, hiszen a telekommunikációban használt három, S, C, és L telekommunikációs sáv mindegyikének optikai erősítésére nagyon jó hatásfokkal képesek [5, 6], kiváltva ezzel a továbbítandó jel újragenerálásához addig használt elektro-optikai átalakítókat. A szélessávú működés ugyanakkor lehetővé teszi e berendezéseknek a rövid impulzusú szállézerekben történő alkalmazását is [7].

1970-ben jól használható, folytonos üzemű, szobahőmérsékleten működő félvezető lézerek jelentek meg a piacon, ami hozzájárult a száloptikás kommunikáció térhódításához. Az erbium-adalékolt szállézerek 1996 óta részei a tenger alatti optikai átviteli rendszereinknek [8]. A nagy teljesítményű lézerrendszerek esetében pedig az EDFA-k továbbfejlesztett változatai, a köpenyben pumpált és itterbiummal mellékadalékolt szálak [9], illetve az extra nagy módusterületű erbium erősítő szálak terjedtek el [10].

Referencia

[1] R. J. Mears, L. Reekie, S. B. Poole, and D. N. Payne: Low-threshold tunable CW and Q-switched fibre laser operating at 1.55 μm; Electronics Letters 22 (1986) 159-160

[2] E. Desurvire, J.R. Simpson, and P.C. Becker: High-gain erbium-doped traveling-wave fiber amplifier; Optics Letters 12 (1987) 11

[3] C. J. Koester and E. Snitzer: Amplification in a fiber laser; Applied Optics 3 (1964) 1182

[4] E. Desurvire: Erbium-doped fiber amplifiers for new generations of optical communication systems; Optics and Photonics News 2 (1991) 6-

[5] E. Desurvire, C. R. Giles, J. R. Simpson, and J. L. Zyskind: Efficient erbium-doped fiber amplifier at a 1.53-μm wavelength with a high output saturation power; Optics Letters 14 (1989) 1266-1268

[6] T. Kashiwada, M. Shigematsu, T. Kougo, H. Kanamori, and M. Nishimura: Erbium-doped fiber amplifier pumped at 1.48 mu m with extremely high efficiency; IEEE Photonics Technology Letters 3 (1991) 721-723

[7] J. D. Kafka, T. Baer, and D. W. Hall: Mode-locked erbium-doped fiber laser with soliton pulse shaping; Optics Letters 14 (1989) 1269-1271

[8] S. Ash: Happy Birthday EDFA; https://atlantic-cable.com/Article/SA/57/index.htm

[9] J. D. Minelly, W. L. Barnes, R. I. Laming, P. R. Morkel, J. E. Townsend, S. G. Grubb, and D. N. Payne: Diode-array pumping of Er3+/Yb3+ co-doped fibre lasers and amplifiers; IEEE Photonics Technology Letters, 5 (1993) 301-303

[10] J. C. Jasapara, M. J. Andrejco, A. DeSantolo, A. D. Yablon, Z. Várallyay, J. W. Nicholson, J. M. Fini, D. J. DiGiovanni, C. Headley, E. Monberg, and F. V. DiMarcello: Diffraction-limited fundamental mode operation of core-pumped very-large-mode-area Er fiber amplifiers; IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics 15 (2009) 3-11

References

[1] R. J. Mears, L. Reekie, S. B. Poole, and D. N. Payne: Low-threshold tunable CW and Q-switched fibre laser operating at 1.55 μm; Electronics Letters 22 (1986) 159-160

[2] E. Desurvire, J.R. Simpson, and P.C. Becker: High-gain erbium-doped traveling-wave fiber amplifier; Optics Letters 12 (1987) 11

[3] C. J. Koester and E. Snitzer: Amplification in a fiber laser; Applied Optics 3 (1964) 1182

[4] E. Desurvire: Erbium-doped fiber amplifiers for new generations of optical communication systems; Optics and Photonics News 2 (1991) 6-

[5] E. Desurvire, C. R. Giles, J. R. Simpson, and J. L. Zyskind: Efficient erbium-doped fiber amplifier at a 1.53-μm wavelength with a high output saturation power; Optics Letters 14 (1989) 1266-1268

[6] T. Kashiwada, M. Shigematsu, T. Kougo, H. Kanamori, and M. Nishimura: Erbium-doped fiber amplifier pumped at 1.48 mu m with extremely high efficiency; IEEE Photonics Technology Letters 3 (1991) 721-723

[7] J. D. Kafka, T. Baer, and D. W. Hall: Mode-locked erbium-doped fiber laser with soliton pulse shaping; Optics Letters 14 (1989) 1269-1271

[8] S. Ash: Happy Birthday EDFA; https://atlantic-cable.com/Article/SA/57/index.htm

[9] J. D. Minelly, W. L. Barnes, R. I. Laming, P. R. Morkel, J. E. Townsend, S. G. Grubb, and D. N. Payne: Diode-array pumping of Er3+/Yb3+ co-doped fibre lasers and amplifiers; IEEE Photonics Technology Letters, 5 (1993) 301-303

[10] J. C. Jasapara, M. J. Andrejco, A. DeSantolo, A. D. Yablon, Z. Várallyay, J. W. Nicholson, J. M. Fini, D. J. DiGiovanni, C. Headley, E. Monberg, and F. V. DiMarcello: Diffraction-limited fundamental mode operation of core-pumped very-large-mode-area Er fiber amplifiers; IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics 15 (2009) 3-11

The 1971 Nobel Prize in Physics

Az 1971-es fizikai Nobel-díj

>The 1971 Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to Dénes Gábor (Dennis Gabor) for his invention and development of the holographic method.

The British engineer-physicist of Hungarian descent developed the theory of a technique that provides a perfect 3D image of the structure of the object to be captured. His method is based on the wave nature and interference of light.

Az 1971-es fizikai Nobel-díjat a holografikus módszer feltalálásáért és kifejlesztéséért Gábor Dénesnek ítélték oda.

A magyar származású, brit állampolgárságú mérnök-fizikus egy olyan képalkotási eljárás elvét alkotta meg, amely tökéletes térhatású leképezést ad a rögzítendő tárgyak struktúrájáról. Módszere a fény hullámtermészetén, a fényhullámok interferenciáján alapul.

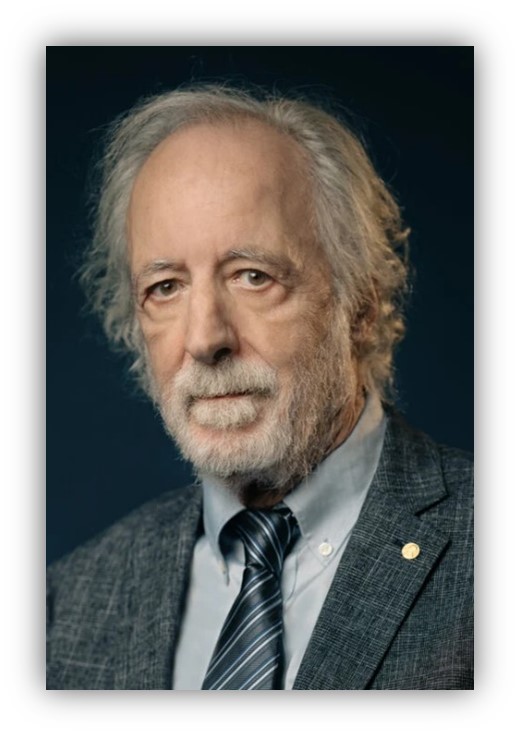

Dénes Gábor

(Source: the archives of the Nobel Foundation)Gábor Dénes

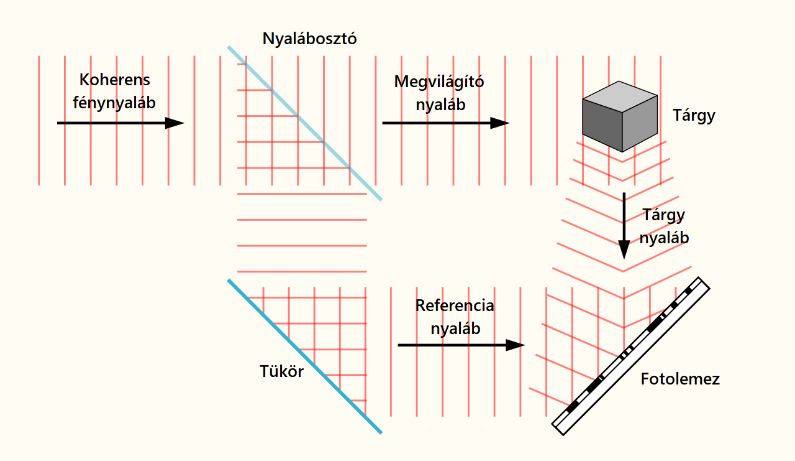

(Forrás: a Nobel Alapítvány archívuma)Traditional photography records only the colour and intensity of the light waves, while holography is also able to record their phase, and thus stores depth information in the “image”.

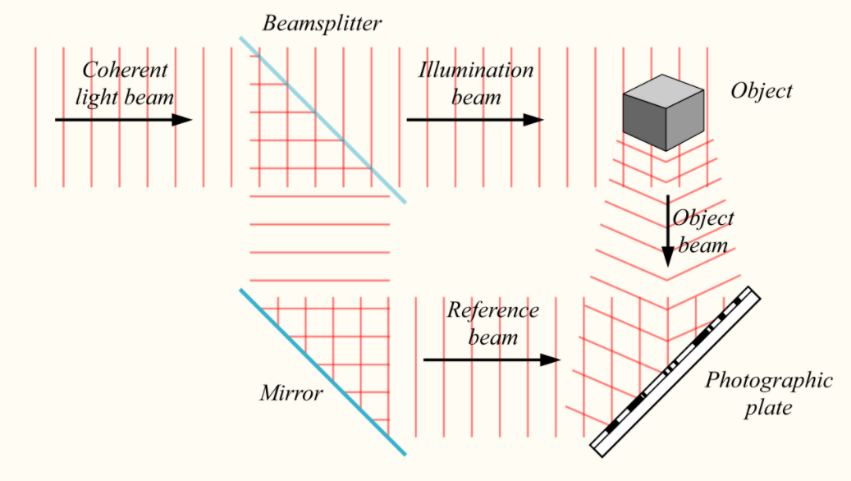

When a hologram is made, a change in phase is encoded as a change in intensity, i.e. it is made detectable. Encoding can be implemented through interference, but in addition to the light wave originating from the object to be captured, the process requires another, coherent light source – a laser – that is able to interfere. A light source (a multitude of electromagnetic waves) is coherent if the electric field of the individual light beams vibrates in the same phase. This creates interference during which at different points in space the waves with a constant phase strengthen or weaken one another to varying extents. Consequently, the intensity fluctuation of the final image also depends on the phase difference of the interfering light waves. When suitably illuminated, the developed holographic plate “reconstructs” – through the bending or diffraction of light – both the intensity and phase distribution of the light scattered from the object, and therefore a 3D image is produced.

A hagyományos fotográfia csupán a fényhullámok színét és intenzitását, míg a holográfia azok fázisát is képes rögzíteni, és ezzel mélységinformációt tárol a „képben”.

Hologram készítésekor a fázisváltozást intenzitásváltozásként kódoljuk, vagyis a detektor számára érzékelhetővé tesszük. A kódolás megvalósítására az interferencia jelensége alkalmas, ehhez viszont a rögzítendő tárgyról kiinduló fényhullámon kívül egy másik, nagy koherenciájú, következésképpen interferenciaképes fényforrásra – lézerre – is szükség van. Egy fényáram (mint elektromágneses hullámok sokasága) akkor koherens, ha az egyes fénynyalábok elektromos tere azonos fázisban rezeg. Ilyenkor interferencia alakul ki, amelynek során a tér különböző pontjain az állandó fáziskülönbségű hullámok egymást eltérő mértékben erősítik vagy gyengítik. Az eredő kép intenzitásingadozása tehát az interferáló fényhullámok fáziskülönbségétől is függ. Megfelelő megvilágítással a kidolgozott hologramlemez a fényelhajlás (idegen szóval diffrakció) révén „rekonstruálja” a tárgyról szórt fény intenzitás- és fáziseloszlását, így a látvány térbelivé válik.

Holografikus kép rögzítésének elrendezési elve

(Forrás: Wikipedia)Optical setup for recording a hologram

(Source: Wikipedia)

Holografikus kép rekonstruálásának elrendezési elve

(Forrás: Wikipedia)Optical setup for the reconstruction of a holographic image Although the theory of holography was developed already in 1947, it could only be translated into reality in 1961 (after lasers became available), because earlier light sources were not sufficiently coherent to produce interference.

The most common application of holography is in the form of security hologram stickers (e.g. on banknotes, credit/debit cards, CDs), but its use ranges from information storage through interference experiments to holographic filming.

Bár a holográfia elvét Gábor Dénes már 1947-ben megalkotta, a megvalósításra egészen 1961-ig (a lézerek elérhetővé válásáig) kellett várni. Korábban ugyanis nem állt rendelkezésre olyan fényforrás, amely az interferencia előállításához szükséges koherenciát biztosítani tudta volna.

A holográfia alkalmazási formái közül leggyakrabban a biztonsági azonosító jelekkel találkozhatunk (például papírpénzeken, bankkártyákon, CD-ken), de felhasználási területei az információtárolástól az interferencia-kísérleteken át a holografikus filmezésig terjednek.

Hologram foil strips are incorporated into Hungarian banknotes too,

to the left from the denomination and other words

(Source: mnb.hu)Hologramfólia-csík található a magyar bankjegyeken is,

a középső feliratoktól balra

(Forrás: mnb.hu)

Referencia

[1] Gábor Dénes: Holography, 1948-1971; Nobel lecture, 1971.

[2] Gábor Dénes: Holográfia, 1948-1971; Fizikai szemle 2000/6. 181.o.

References

[1] Gábor Dénes: Holography, 1948-1971; Nobel lecture, 1971.

[2] Gábor Dénes: Holográfia, 1948-1971; Fizikai szemle 2000/6. 181.o.

The 1981 Nobel Prize in Physics

Az 1981-es fizikai Nobel-díj

The Nobel Prize in Physics 1981 was divided, with one half awarded jointly to Nicolaas Bloembergen and Arthur L. Schawlow "for their contribution to the development of laser spectroscopy" and the other half to Kai M. Siegbahn "for his contribution to the development of high-resolution electron spectroscopy."

Az 1981-es fizikai Nobel-díjat a lézerspektroszkópia és a nagyfelbontású elektronspektroszkópia területén elért úttörő eredményekért ítélték oda. Az elismerést megosztva Nicolaas Bloembergen és Arthur L. Schawlow, illetve Kai M. Siegbahn kapta.

The concept of quantum mechanics made it possible to understand that the electrons of atoms and molecules can only exist at well-defined energy levels. When excited, i.e. by taking on a photon’s energy (absorption), electrons may get into a higher energy level from where they can return to the ground (or a lower) energy state spontaneously or upon stimulation. During this, they release a photon (emission). As the energy levels are constant, the energy of the photon absorbed or emitted in the transitions (the difference between the two energy levels) is also constant.

In spectroscopic studies, the chemical compositions of samples can be determined through the mapping of these transitions, by identifying the spectroscopic lines belonging to the transitions.

Schawlow developed a procedure which utilized the high intensity of laser light to eliminate the broadening of the spectral lines due to the motion of the atoms. This significantly improved the accuracy of spectroscopic measurements, and the energy levels of hydrogen – as the simplest element – could be measured with an unprecedented degree of precision. Thanks to the procedure, the value of the Rydberg constant, one of the most fundamental constants, could also be determined with higher precision.

Bloembergen invented and implemented a procedure in which three different laser lights were mixed to produce a fourth one. The wavelength of this new light was significantly outside the wavelength range of lasers built before, as a result of which spectroscopic studies could be conducted in a significantly broader frequency range. Spectroscopic studies using such lasers were applied in diverse fields ranging from the optimization of internal combustion engines to the analysis of the transport processes of biological samples.

With sufficient excitation, an electron can even be removed from the atom or the molecule. Since the energy of the detached electron equals the difference between the photon energy and the electron’s binding energy, the electron’s binding energy inside the atom can be determined by measuring the energy of the detached electrons – with the so-called electron spectroscopy method, if the experiment is conducted with monochromatic light (i.e. with photons having the same energy). The further development of electron spectroscopy has allowed scientists to identify not only the atoms included in a sample, but also to determine in which chemical environment these atoms exist.

Through systemic studies carried out at the end of the 1950s, Siegbahn and co-workers determined the binding energies of electrons in chemical elements. Their work significantly influenced the development of the electron spectroscopy method, and their measurements form an important database.

A kvantummechanikai tárgyalásmód lehetővé tette annak megértését, hogy az atomok és molekulák elektronjai csak jól meghatározott energiájú állapotokat vehetnek fel. Az elektronok gerjesztés – foton felvétele (abszorpció) – hatására magasabb energiájú állapotba kerülhetnek, és onnan spontán vagy kényszer hatására visszakerülhetnek az alap (vagy alacsonyabb) energiájú állapotba egy foton kibocsátásával (emisszió). Mivel az energiaszintek meghatározottak, ezért a közöttük lévő átmenetben elnyelt illetve kisugárzott foton energiája (a két szint közti energiakülönbség) is jól definiált.

A spektroszkópiai vizsgálatokban ezen átmenetek feltérképezése révén ismerhető meg a minták kémiai összetétele, azonosítva a színképben az átmenetekhez tartozó vonalakat.

Schawlow olyan eljárást fejlesztett ki, amelyben a lézerfény alkalmazásával – annak nagy intenzitása révén – ki tudta küszöbölni a spektrumvonalak atomok mozgásából eredő kiszélesedését. Ez jelentősen növelte a spektroszkópiai mérések pontosságát, és így rendkívüli precizitással mérhetővé váltak a hidrogén – mint legegyszerűbb elem – energiaszintjei. A kísérlet végeredményeként az egyik legalapvetőbb atomi konstans, a Rydberg-állandó értékét is pontosíthatták.

Bloembergen egy olyan eljárást dolgozott ki és valósított meg, amelyben három lézerfény keverésével egy negyediket lehet előállítani. Ennek a hullámhossza messze kívül esett az addig megvalósítható lézerfények tartományától, így a spektroszkópiai vizsgálatok lényegesen szélesebb frekvenciatartományban váltak elvégezhetővé. Az ilyen lézerekkel történő spektroszkópiai vizsgálatok igen változatos területeken jelentek meg, a belsőégésű motorok működésének optimalizálásától egészen a biológiai szövetminták transzportfolyamatainak vizsgálatáig.

Megfelelő gerjesztéssel az elektron le is szakítható az atomról vagy molekuláról. Mivel a leválasztott elektron energiája a foton energiájának és az elektron kötési energiájának különbsége, monokromatikus fénnyel (azaz azonos energiájú fotonokkal) végezve a kísérletet, a leválasztott elektronok energiájának mérésével – úgynevezett elektronspektroszkópiával - meghatározható azok atombeli kötési energiája. Az elektronspektroszkópia továbbfejlesztésével nemcsak az állapítható meg, hogy egy mintában milyen atomok találhatók, hanem az is, hogy ezek milyen kémiai környezetben vannak.

Siegbahn és munkatársai az 50-es évek végén szisztematikus kutatásaikkal kémiai elemek elektronjainak kötési energiáit határozták meg. Munkájuk nagy hatással volt az elektronspektroszkópiai módszer fejlődésére, és mért eredményeik fontos adatbázist alkotnak.

Referencia

https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/1981/summary/

References

https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/1981/summary/

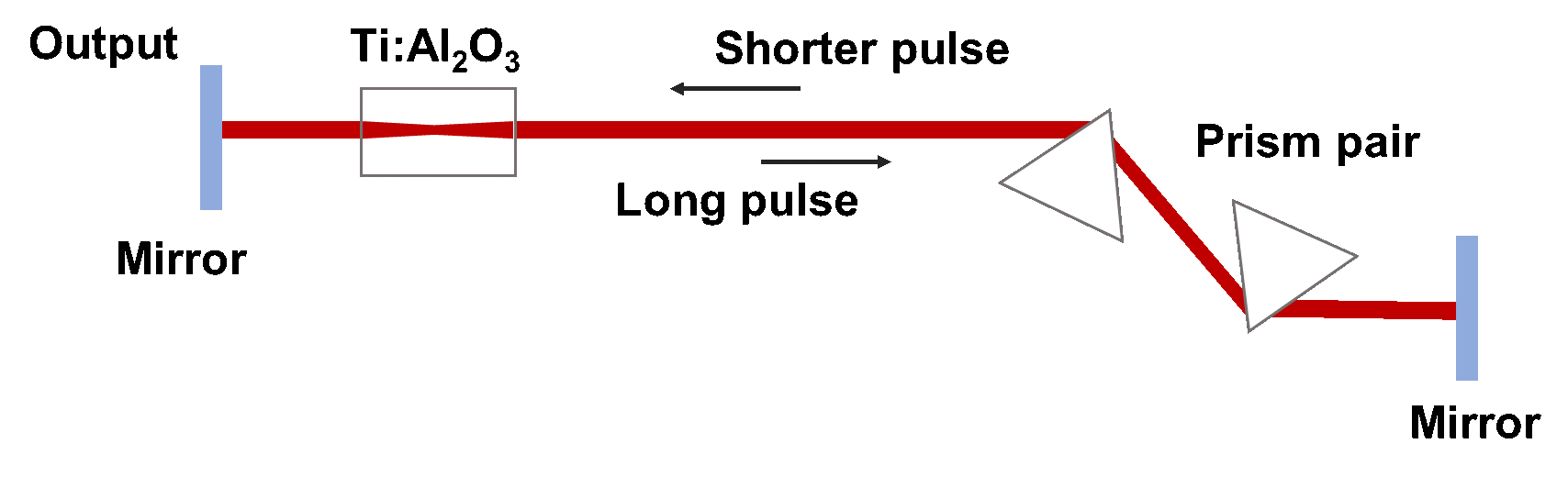

The First Sub 100 Femotosecond Laser

Az első 100 fs alatti lézerimpulzusok

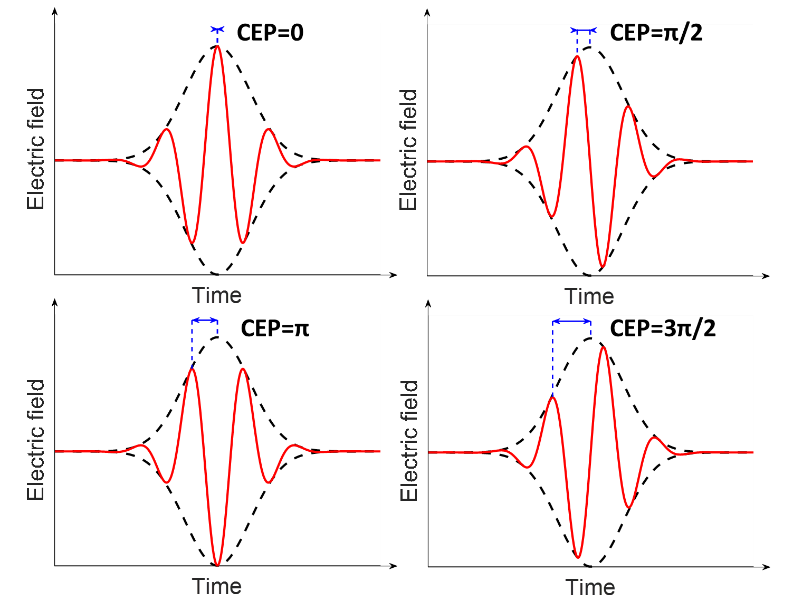

>The peak power of laser pulses can be enhanced in two ways: either by increasing the energy of the laser pulse, or by shortening the pulse in time. Until the mid 1970s, the latter effect was mostly achieved by chopping the laser beam by mechanical or electrical means. However, due to the speed constraints of these processes, the pulse length could only be reduced to the sub-nanosecond range.

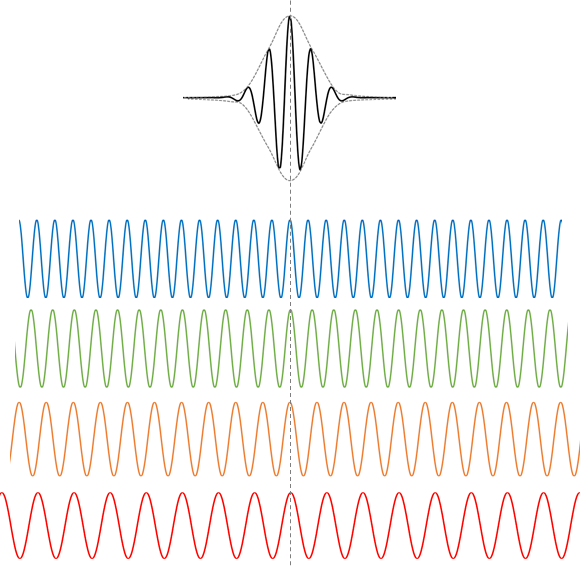

To achieve an even shorter length, the process itself had to be shortened (in a passive manner). To this end, we need to go back to the fundamental laws of physics, more precisely to the Heisenberg uncertainty principle. Because the shorter the desired light pulse, i.e. the more accurate the time measurement is, the less “accurately” we are able to define the colour of the light pulse, wherefore the spectrum of the light pulse becomes wider and wider. The dye lasers that first appeared in the 1970s and 1980s exploited this phenomenon. Excited dyes can emit light in a wide spectrum due to their complex molecule structure. Since the opposite of the former statement is also true, the broader the spectrum in which light can be emitted, the shorter the light pulse one can achieve by means of compression.

Apart from coherence caused by stimulated emission, another precondition for compression is that the light waves of different colours, emitted by the laser, should meet in the same phase. This happens if they travel their circular path in the resonator within the same time.

In matter (e.g. glass or air) the light rays of the component colours travel at different velocities. Yet, to achieve a short light pulse, the component colours must “see” the same optical path, i.e. the product of the refractive index and the geometric length must be identical. This can be achieved by inserting into the resonator optical elements with proper (often negative) dispersion, such as a prism (pair), a grating (pair), a chirped mirror (invented later). This process is called mode-locking.

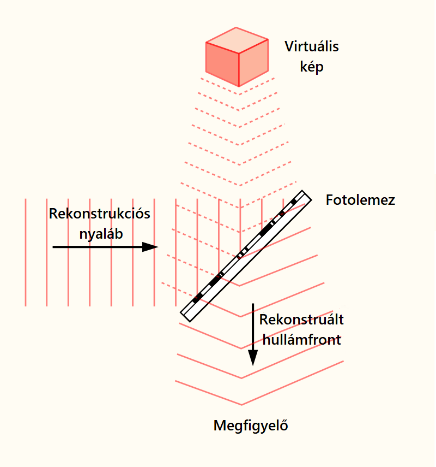

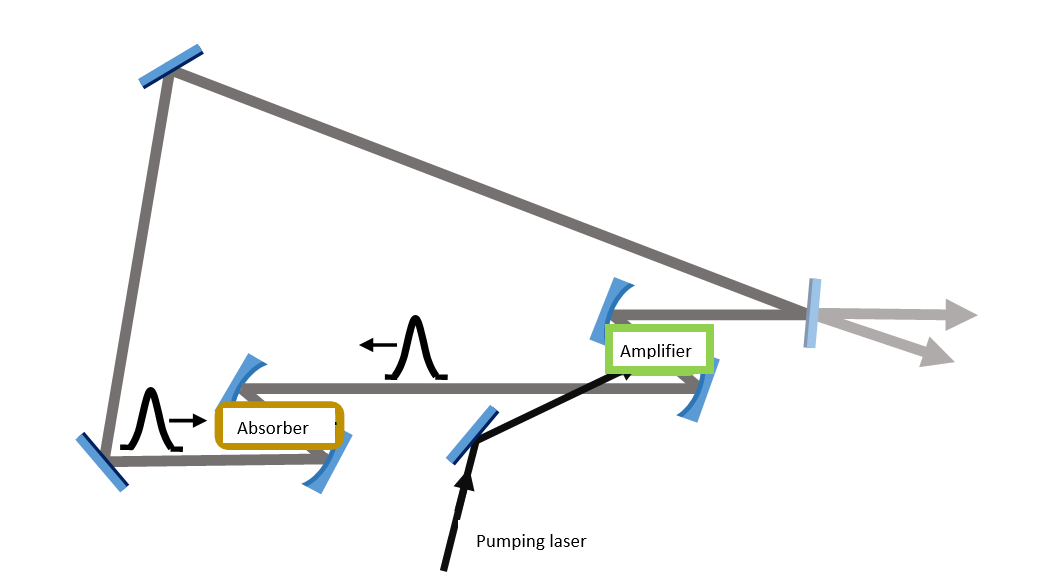

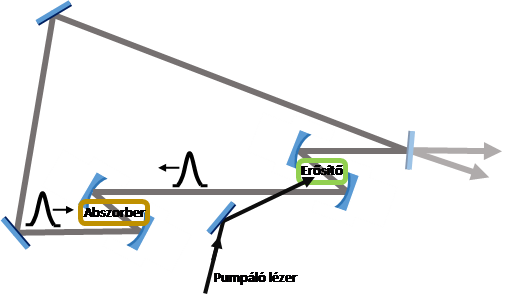

The first laser pulse below 1 ps was achieved with such a passively mode-locked dye laser in 1974 [1]. The next significant step was the development of the colliding pulse mode-locked (CPM) laser in 1981 [2], which was able to generate the first sub-100 fs light pulse.

In a CPM laser, two pulses travelling in opposite directions (clockwise and anti-clockwise) meet (collide) in the saturable absorber, so the saturation loss for the two pulses is lower, hence light amplification in the dye is more efficient. The interaction between the pulses propagating opposite each other create a temporary grating in the multitude of absorbing molecules, which mode-locks, stabilizes and shortens the pulses propagating in both directions.

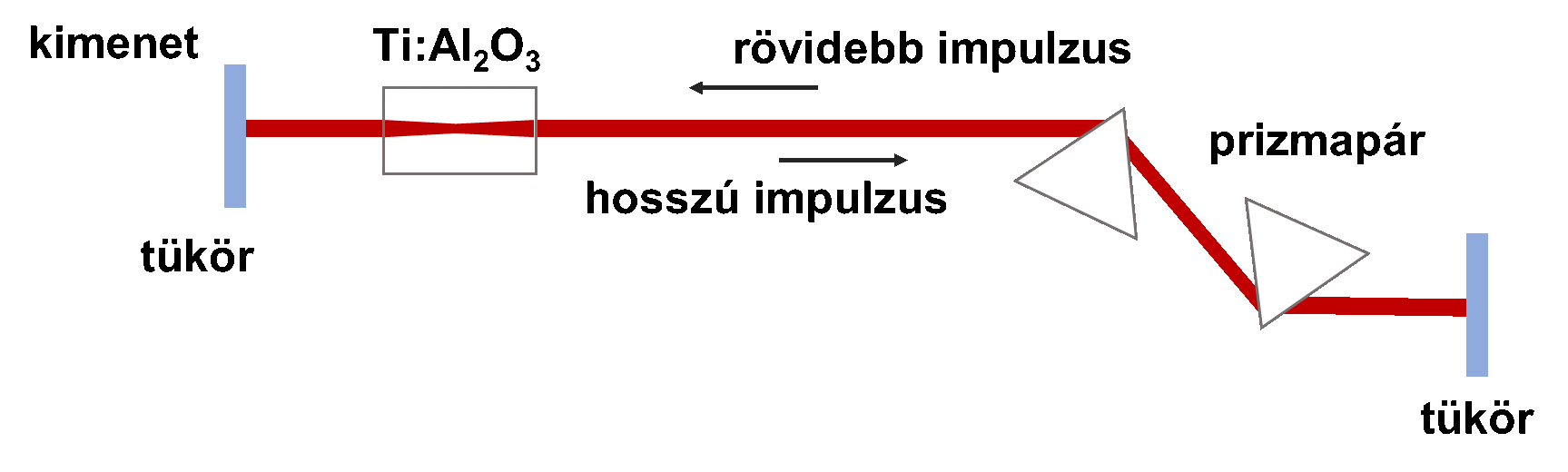

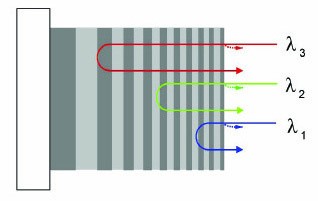

The laser is arranged in a ring configuration (see figure), because pulse collision must be very accurate, and in contrast with a straight resonator the pulses that travel opposite each other mode-lock themselves, there is no need for the active stabilization of timing.

A lézerimpulzusok csúcsteljesítménye kétféleképpen fokozható: vagy a lézerimpulzus energiájának növelésével, vagy pedig időbeli hosszának rövidítésével. Az utóbbit a hetvenes évek derekáig főleg a lézerműködés mechanikai vagy elektromos szaggatásával érték el, de e folyamatok sebességkorlátai miatt maximum szub-nanoszekundum nagyságrendig sikerült az impulzushosszt csökkenteni.

Ha ennél rövidebbre szeretnénk jutni, valamiképpen magát a folyamatot önmagában (passzívan) kell rábírni arra, hogy rövid legyen. Ehhez a fizika alaptörvényeihez, egész pontosan a Heisenberg-féle határozatlansági relációig is le kell nyúlni. Mert minél rövidebb időbeli felvillanást szeretnénk elérni, azaz minél pontosabban akarunk időt mérni, annál „pontatlanabbul” tudjuk meghatározni a fényimpulzus színét; szükségképpen a fényimpulzus színképe (spektruma) egyre szélesebbé válik. A 70-es és 80-as években megjelent festéklézerek pontosan ezt a jelenséget használták ki. A gerjesztett festékek összetett molekulaszerkezetük miatt széles spektrumban képesek fényt kibocsátani. Mivel az előző állítás fordítva is igaz, minél szélesebb spektrumban vagyunk képesek fényt kibocsátani, annál rövidebb fényimpulzussá tudjuk azt összenyomni.

A kényszerített emisszió okozta koherencián túl az összenyomás további feltétele, hogy a lézer által kibocsátott különböző színű fényhullámok azonos fázisban találkozzanak. Ez akkor teljesül, ha ezek a rezonátorban ugyanannyi idő alatt járnak körbe.

Anyagokban (például üvegben, levegőben) terjedve a fény különböző színű összetevőinek más és más a sebessége. Ennek ellenében egy rövid fényimpulzus előállításához azt kell elérni, hogy a fény színei azonos optikai úthosszt lássanak, azaz a törésmutató és a térbeli hossz szorzata állandó legyen. Ez a lézer rezonátorába helyezett megfelelő (sok esetben negatív) diszperziójú optikai elemek, például prizma(pár), rács(pár), illetve a később feltalált csörpölt tükör segítségével érhető el. Ezt a folyamatot nevezzük módusszinkronizációnak.

Az első pikoszekundumnál rövidebb lézerimpulzust 1974-ben [1] is ilyen passzívan módusszinkronizált festéklézerrel sikerült elérni. A következő jelentős lépés az ütköző impulzusokkal módusszinkronizált (angolul colliding pulse mode-locked, rövidítve CPM) lézer kifejlesztése volt 1981-ben [2], amellyel 100 fs-nál valamivel rövidebb impulzusokat állítottak elő.

A CPM lézerben két, egymással szemben haladó impulzus a telíthető fényelnyelőben találkozik („ütközik”), így a két impulzusra nézve kisebb az elnyelés telítésére fordított veszteség, ami hatékonyabb fényerősödéshez vezet a festékben. A két szemben terjedő impulzus közötti kölcsönhatás egy ideiglenes rácsot hoz létre az abszorber molekulák sokaságában, amely módusszinkronizálja, stabilizálja és lerövidíti a mindkét irányba terjedő impulzusokat.

A lézer elrendezése az ábrának megfelelően gyűrű alakú, ugyanis az impulzusütköztetésnek nagyon pontosnak kell lennie, és egy egyenes rezonátorhoz képest itt az egymással szemben haladó impulzusok „önmaguktól” szinkronizálódnak, nincs szükség az időzítés aktív stabilizálásra.

Configuration of a ring CPM dye laser

Gyűrűs elrendezésű CPM festéklézer felépítése

Referencia

[1] C. V. Shank, E. P. Ippen: Subpicosecond kilowatt pulses from a mode-locked cw dye laser; Appl. Phys. Lett. 24 (1974) 373

[2] R. L. Fork, B. I. Greanl, C. V. Shank: Generation of optical pulses shorter than 0.1 psec by colliding pulse mode locking;

Appl. Phys. Lett. 38 (1981) 671

References

[1] C. V. Shank, E. P. Ippen: Subpicosecond kilowatt pulses from a mode-locked cw dye laser; Appl. Phys. Lett. 24 (1974) 373

[2] R. L. Fork, B. I. Greanl, C. V. Shank: Generation of optical pulses shorter than 0.1 psec by colliding pulse mode locking;

Appl. Phys. Lett. 38 (1981) 671Observation of high-order harmonics created in a plasma

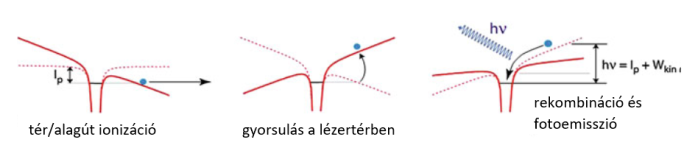

Magasharmonikus-keltés plazmában

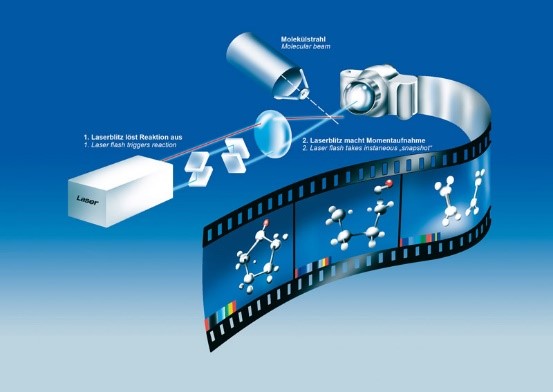

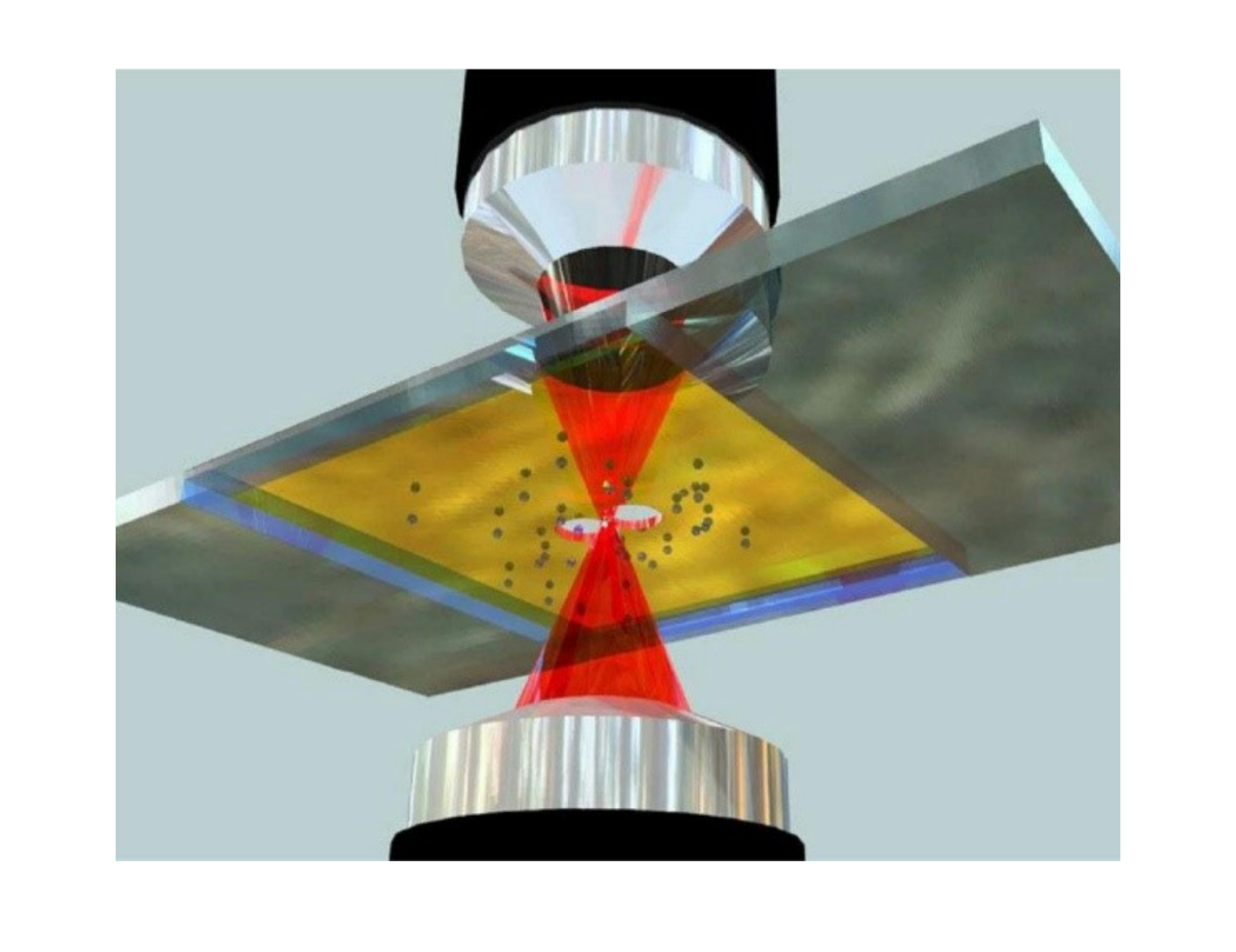

Albert Einstein was the first to predict the frequency up-conversion of light by reflection from a mirror, moving near light speed, as early as in 1905 [1]. Although the concept of relativistic surfaces seemed promising, it could not be implemented before the advent of intense ultrashort lasers (2018 Nobel Prize in Physics) which can generate plasma surfaces moving at light speed. This is a key element for modern day laser plasma interactions. The first laboratory demonstration of high-order harmonics generation, which is the basis for any attosecond pulse generation, was performed in high intensity laser interactions with surface plasma by scientists of Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory during 1980–1981 [2]. Carman et al (Gemini Laser Facility, UK) focused high power carbon dioxide laser pulses with duration of ~ 1 ns during an inertial confinement fusion experiment on a plastic and metal coated glass micro-balloon targets. As a result of the laser plasma interaction, high-order harmonics generation was observed up to the 29th order in the back-scattered direction. A carbon dioxide laser has a wavelength of 10 µm. Hence, the generated high-order harmonics are in the visible spectrum of the electromagnetic radiation. Few months later, the experiment was repeated using another carbon dioxide laser with a laser pulse duration of < 200 ps. This time high-order harmonics generation was observed up to the 46th order [3]. These two experiments are widely recognized as the first demonstration of high-order harmonic generation from a surface plasma. However, another experiment published by N.H. Burnettat et. al., in 1977 demonstrated the first harmonics generation up to 11th order of a high power carbon dioxide laser [4] and deserve honourable mention in this context.

Later, in 1987, high-order harmonics generation was demonstrated from a gas target. At this time, scientists were already able to generate electromagnetic pulses of attosecond (10–18> second) duration, which allows for the investigation of ultrafast processes e.g. in condensed matter or biological samples at molecular or atomic scale.

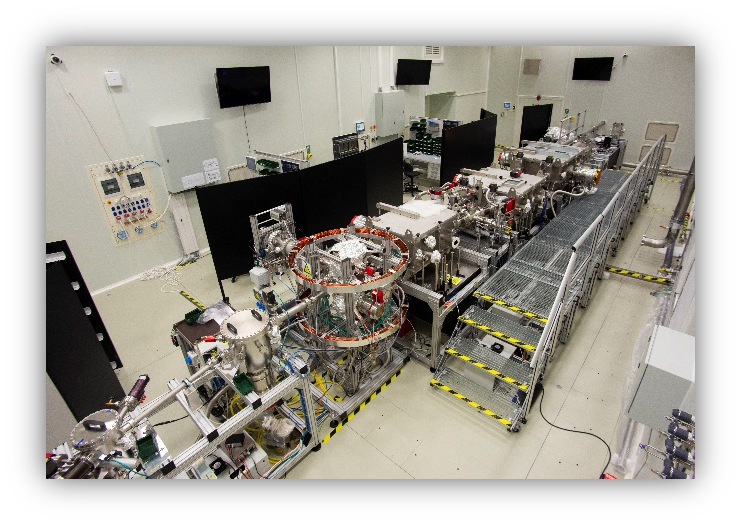

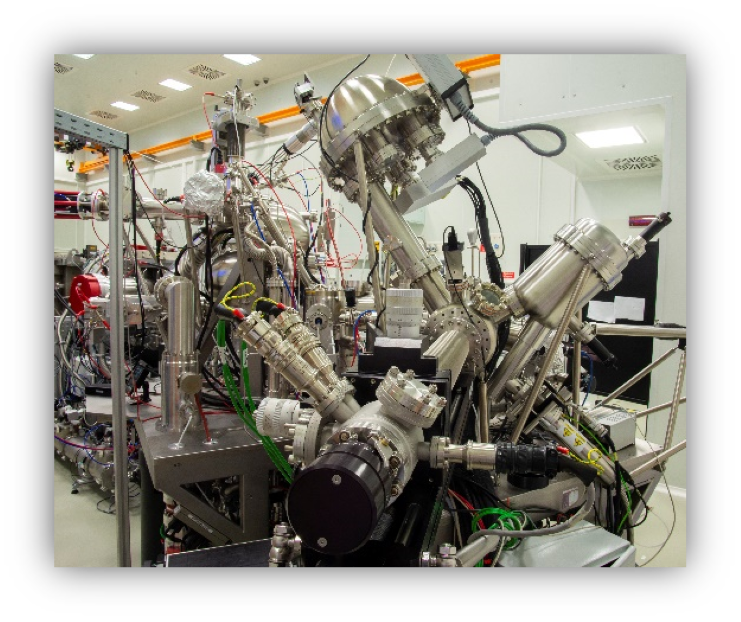

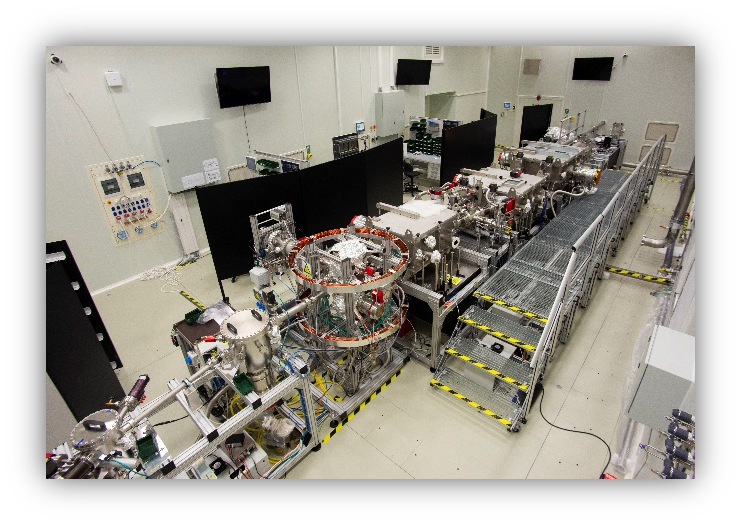

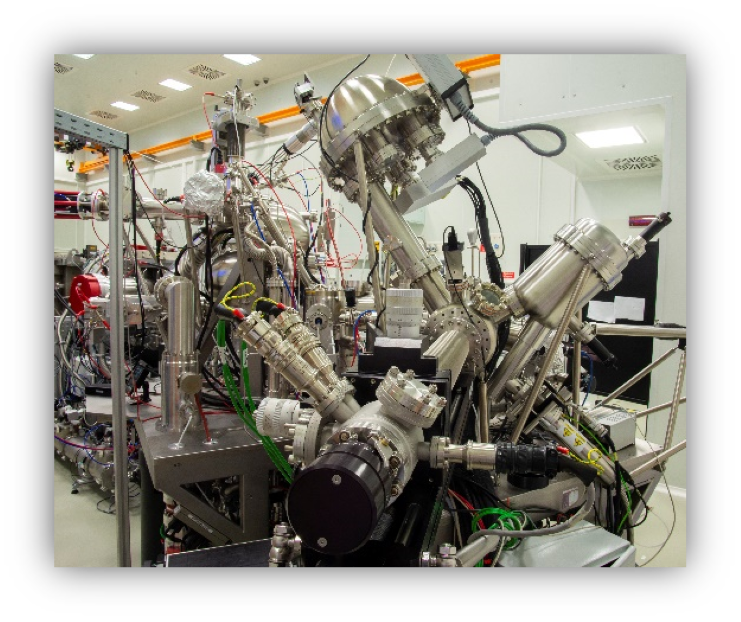

Presently, there are several laboratories around the world that show interest in attosecond light pulse generation by the above mentioned technique. Among several beamlines, which are being developed under the Secondary Sources Division at ELI ALPS, there are two attosecond beamlines (SHHG-SYLOS and SHHG-HF) [6,7] which will take advantage of attosecond pulse generation by the high-intensity interaction of laser with surface plasma, and are expected to set new directions in attosecond research and particle acceleration as well as provide for user experiments [5].

Albert Einstein volt az első, aki felvetette – már 1905-ben –, hogy a közel fénysebességgel haladó tükörről visszaverődő fény frekvenciája felkonvertálódik. Bár a relativisztikus felületek koncepciója ígéretesnek tűnt, kísérleti megvalósításuk a fénysebességgel haladó plazmafelület létrehozására képes nagy teljesítményű, ultrarövid lézerek megjelenéséig váratott magára [2]. Laboratóriumi körülmények között a Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory kutatói 1980-81-ben demonstrálták az attoszekundumos impulzusok előállításához szükséges magasharmonikus-keltést lézerfény és felületi plazma nagy intenzitású kölcsönhatásával [2]. Carman és munkatársai nagy energiájú széndioxid lézer segítségével ~ 1 ns hosszúságú lézerimpulzusokat műanyag és fémbevonatú üveg mikrogömb céltárgyakra fókuszálták inertial confinement fúziós (IFC) kísérletekben. A lézer-plazma kölcsönhatás eredményeként a visszaszórásban még a 29. felharmonikuskeltés is megfigyelhető volt. A széndioxid lézer hullámhossza 10 mikron, ezért a keltett magasharmonikusok az elektromágneses sugárzás látható tartományába esnek. A kísérletet néhány hónappal később megismételték egy másik széndioxid-lézer < 200 ps hosszúságú lézerimpulzusaival. Ez alkalommal a 46-ik rendig figyeltek meg magasharmonikus keltést [3]. Ezt a két kísérlet széles körben a felületi plazmából történő magasharmonikus-keltés első demonstrációjának tartják. Ugyanakkor fontos megemlítenünk, hogy N.H. Burnettat és munkatársai 1977-ben egy másik kísérletről számoltak be, amelyben a 11-ik rendig demonstrálták a magasharmonikus-keltést nagy teljesítményű széndioxid-lézerrel [4].

Később, 1987-ben, gáz céltárgyon demonstrálták a magasharmonikus-keltést. Ekkor a tudomány már attoszekundum (10–18 másodperc) hosszúságú elektromágneses impulzusok előállítására is képes volt, ami lehetővé teszi ultragyors folyamatok molekuláris vagy atomi szintű tanulmányozását pl. kondenzált anyagokban és biológiai mintákban.

Jelenleg több laboratórium érdeklődik a fenti technikával történő attoszekundumos impulzuskeltés iránt világszerte. Az ELI ALPS Másodlagos Források Osztályán fejlesztés alatt álló sugárforrások között két attoszekundumos sugárforrás (SHHG-SYLOS és SHHG-HF) [6, 7] is van, amelyek kihasználják az attoszekundumos impulzusok és a felületi plazma nagy intenzitású kölcsönhatását, és várhatóan új irányokat jelölnek ki az attoszekundumos kutatások és a részecskegyorsítás területén, valamint kísérletek végzését teszik lehetővé külső felhasználók részére. E kutatások jelentik az ELI ALPS Felületi Plazma Attoforrások Csoport (Surface Plasma Attosources – SPA) kísérleti tevékenységének központi elemét.

Referencia

[1] Einstein, A. Zur Elektrodynamik bewegter Körper (German). Annalen der Physik 322 (1905) 891–921

[2] R. L. Carman, D. W. Forslund, and J. M. Kindel; Phys. Rev. Lett. 46 (1981) 29

[3] R. L. Carman, C. K. Rhodes, and R. F. Benjamin; Phys. Rev. A 24 (1981) 2649

[4] N. H. Burnett, H. A. Baldis, M. C. Richardson, and G. D. Enright; Appl. Phys. Lett. 31 (1977) 172

[5] S. Mondal, et al; J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 35 (2018) A93

References

[1] Einstein, A. Zur Elektrodynamik bewegter Körper (German). Annalen der Physik 322 (1905) 891–921

[2] R. L. Carman, D. W. Forslund, and J. M. Kindel; Phys. Rev. Lett. 46 (1981) 29

[3] R. L. Carman, C. K. Rhodes, and R. F. Benjamin; Phys. Rev. A 24 (1981) 2649

[4] N. H. Burnett, H. A. Baldis, M. C. Richardson, and G. D. Enright; Appl. Phys. Lett. 31 (1977) 172

[5] S. Mondal, et al; J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 35 (2018) A93

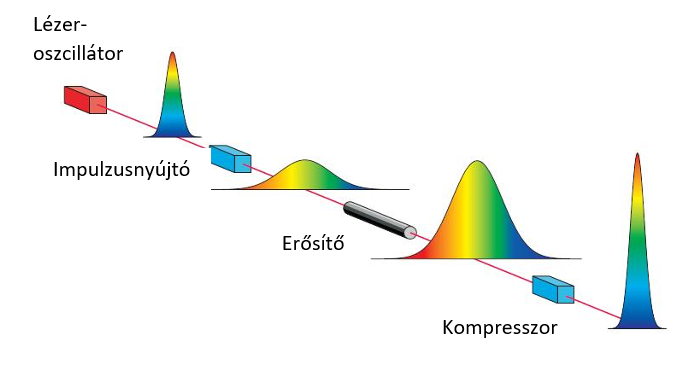

Chirped pulse amplification

Fázismodulált impulzuserősítés

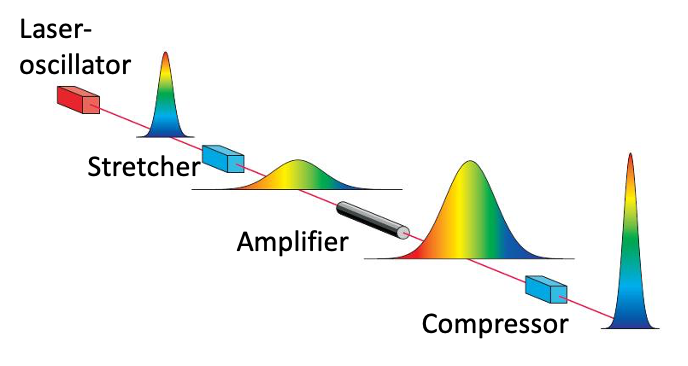

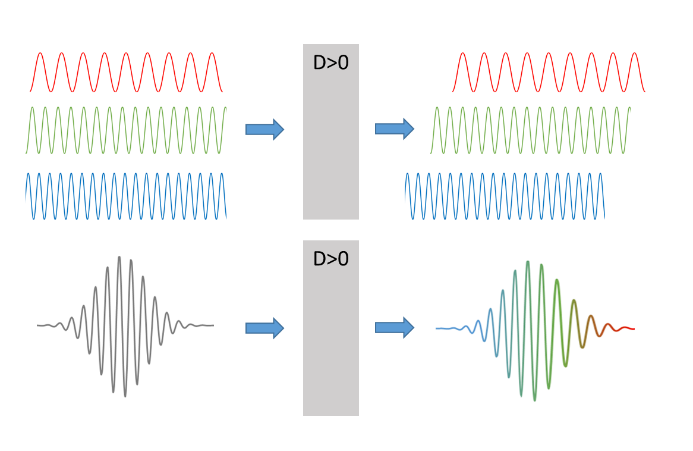

From the invention of lasers [1] up to the early 1970s, the peak power of short laser pulses grew exponentially, but then this trend came to a halt and it seemed that the output of mode-locked laser systems could not be increased beyond a focused intensity of 1014> W/cm2.

The main reason behind this was the phenomenon of self-focusing [2, 3] on the optical elements or in the amplifying medium of the laser. Self-focusing is a nonlinear optical effect as a result of which the medium has a higher refractive index in the more intense part (centre) of the laser beam, and a lower refractive index towards the outer (less intense) parts of the beam. Therefore, the medium practically turns into a focusing lens that may focus the laser beam to an intensity which can damage the medium by filamentation.

A similar problem occurred in the field of radar technology, which also required short and high intensity pulses, but the electrical circuits were unable to handle this intensity. In the case of radars, the issue was solved by sending the pulse through a positive dispersion delay line before amplification and transmission. The return, or echo pulse, would then regain the shape of the original pulse in a negative dispersion delay line [4] (stretching, re-compression). The same technique was used by Donna Strickland and Gérard Mourou for the amplification of intense laser pulses [5], for which they were awarded a shared Nobel Prize in 2019.

This technique has contributed to the rapid growth of laser power, and by now we have surpassed the focused laser intensity of 1025 W/cm2. This technique, in combination with the method of parallel amplification [6], has made it possible to construct the most powerful laser systems of the world at ELI.

A lézerek felfedezésétől [1] az 1970-es évek elejéig exponenciálisan nőtt a rövid lézerimpulzusok csúcsteljesítménye. Ekkor azonban megtorpant ez a tendencia, és úgy tűnt, hogy a 1014 W/cm2-es fókuszált intenzitástartomány fölé már nem emelhető a módusszinkronizált lézerrendszerek teljesítménye.

Ennek fő oka az optikai elemeken vagy a lézer erősítő közegében fellépő nemlineáris önfókuszálódás volt [2, 3]. Ez egy olyan nemlineáris optikai jelenség, amelynek hatására a nyaláb intenzívebb (középső) részén nő, míg a kevésbé intenzív keresztmetszeti területein (szélein) csökken a közeg törésmutatója. Emiatt a közeg fókuszáló lencseként viselkedik, ami a lézernyalábot olyan intenzitásúra fókuszálhatja, hogy az kisülési jelenségeken keresztül roncsolhatja a közeget.

Hasonló probléma merült fel a radartechnológia területén is, ahol szintén rövid és nagy teljesítményű impulzusokra volt szükség a feloldás növeléséhez, de az áramkörök nem tudták kezelni ezt a teljesítményt. A radarok esetén az a megoldás született, hogy erősítés és továbbítás előtt az impulzust egy pozitív diszperzióval bíró késleltető vonalon küldték át. A visszavert hang az eredeti impulzus alakját egy negatív diszperziós késleltető vonalon keresztül nyerte vissza [4] (széthúzás, összenyomás). Ugyanezt a technikát alkalmazta Donna Strickland és Gérard Mourou intenzív lézerimpulzusok erősítésére [5], amiért megosztott Nobel-díjat vehettek át 2018-ben. A lézerek teljesítménye ezzel a technikával rohamos növekedésnek indult és mára már átléphettük a 1025 W/cm2 fókuszált lézerintenzitást is. E technikának és a párhuzamos erősítés módszerének kombinálásával [6] ma a világ legintenzívebb lézerrendszerei működhetnek az ELI-ben.

Chirped pulse amplification (CPA) was first demonstrated [5] by transmitting the Nd:YAG laser pulse to be amplified (150 ps, 5 W, 82 MHz, 0.06 mJ) through a 1.4 km long, single-mode optical fibre with a core diameter of 9 μm. The positive dispersion of this fibre stretched the pulses to 300 ps (this is the phase modulation device) and at the same time, considerably reduced the peak power. After that, the pulses, measured to have a power of 2.3 W at the output of the fibre, were amplified to ~160 W (~2 mJ) in a Nd:glass regenerative amplifier, and finally these pulses were compressed in a double-grating compressor to a pulse width of ~1.5 ps. This method proved suitable to generate pulses with a peak intensity that was unattainable with any amplifier without stretching the pulses and thus avoiding nonlinear self-focusing inside the amplifier.

A fázismodulált impulzusok erősítését (chirped pulse amplification – CPA) legelőször úgy sikerült demonstrálni [5], hogy az erősítendő Nd:YAG lézer impulzust (150 ps, 5 W, 82 MHz, 0,06 mJ) egy 1,4 km hosszúságú, 9 μm magátmérőjű, egymódusú optikai szálon vitték át, amelynek pozitív diszperziója az impulzusokat 300 ps-ra szélesítette ki (ez a fázismoduláló eszköz), és egyben a csúcsteljesítményt lényegesen csökkentette. Majd egy Nd:üveg regeneratív erősítőben a szál kimenetén mért 2,3 W-os impulzusokat ~160 W-ra erősítették (~2 mJ), végül ezeket az impulzusokat egy kétrácsos kompresszorban 1,5 ps körüli impulzusszélességre nyomták össze. Ezzel olyan csúcsteljesítményű impulzusokat állítottak elő, amelyeket erősítőkből nem lehetett volna kinyerni, ha azokat erősítés előtt nem nyújtják ki és nem szüntetik meg a nemlináris önfókuszálódás esélyét.

Referencia

[1] G. A. Mourou, C. L. Labaune, M. Dunne, N. Naumova and V. T. Tikhonchuk: Relativistic laser-matter interaction: from attosecond pulse generation to fast ignition; Plasma Phys. Control. Fusion 49 (2007) B667–B675

[2] P. L. Kelley: Self-focusing of optical beams; Physical Review Letters 15 (1965) 1005–1008

[3] P. Lallemand and N. Bloembergen, Self-focusing of laser beams and stimulated Raman gain in liquids; Physical Review Letters 15 (1965) 1010

[4] E. Brookner: Phased-array radars; Scientific American 252 (1985) 94–103

[5] D. Strickland and G. Mourou: Compression of amplified chirped optical pulses; Opt. Commun., 56 (1985) 219-221

[6] S. Hädrich, M. Kienel, M. Müller, A. Klenke, J. Rothhardt, R. Klas, T. Gottschall, T. Eidam, A. Drozdy, P. Jójárt, Z. Várallyay, E. Cormier, K. Osvay, and A. Tünnermann, J. Limpert: Energetic sub-2-cycle laser with 216 W average power; Optics letters 41 (2017) 4332-4335

References